A Step in the Right Direction and Where Do We Go from Here?

THE AUTHORS:

Isabelle Wenger, Associate at Stephenson Harwood

Ellen Dixon, Associate at Stephenson Harwood

On 24 April 2024, Members of the European Parliament voted, by an overwhelming majority of 560 to 43 (with 27 abstentions), in favour of a European Commission proposal to leave the Energy Charter Treaty (1994) (“ECT“). The decision was adopted by the Council of the European Union on 30 May 2024 following a series of attempts to reform and modernise the ECT.

This coordinated withdrawal by the European Union is considered a watershed moment, following years of debate over how to address an accord that has complicated efforts towards the international community’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and brings them in line with the Paris Agreement (2015).

This article considers:

- Whether the withdrawal from the ECT is a step in the right direction; and

- What next steps, if any, are required to ensure energy disputes are properly handled in the future.

The ECT Withdrawal: A Leap Towards Positive Climate Progression?

The withdrawal “from the climate-wrecking Energy Charter Treaty” can be viewed as a landmark decision when it comes to the European Union progressing towards net zero.

Time for a Different Investment Agreement?

First, the withdrawal from the ECT will likely result in a significant portion of global energy market participants relying on investment agreements that are more progressive. This is in part because the ECT:

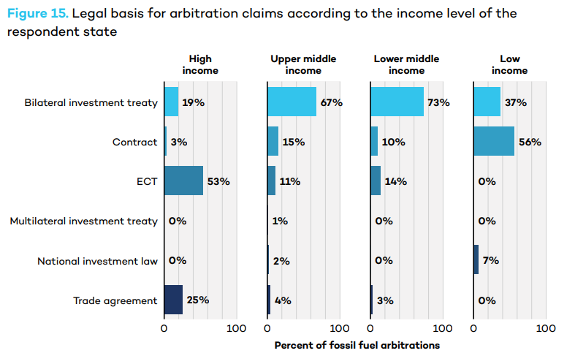

- Is the single most employed international investment agreement in fossil fuel arbitrations; 41 of 42 arbitration claims in the fossil fuel industry that are based on plurilateral investment treaties allege a breach of the ECT;

- Makes up the single highest legal basis (at 53%) for arbitration claims in high-income respondent States, ranking second and third in lower-middle and upper-middle income States respectively; and

- Disproportionately advantages investors, by restricting government freedom to regulate (Article 5) and providing enabling articles that ensure primacy to the ECT (Article 18).

Further, the provisional modernisations to the ECT framework adopted on 3 December 2024, are similarly insufficient – containing too many exceptions and carve-outs to meet the objective the amendments are drafted to achieve, aptly described by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (“IISD“) as “too modest, too piecemeal, and too untested to transform the ECT into an instrument that is compatible with the global climate agenda“.

The “Chilling Effect” on Climate-Friendly Legislation

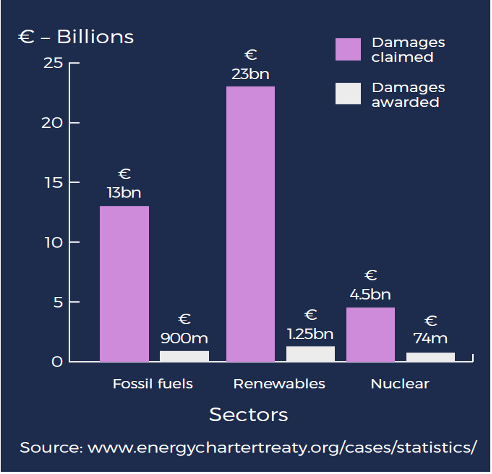

Second, the quantity of damages ordered under the ECT purportedly led to a “chilling effect” that discouraged States from developing “climate-friendly” legislation. The risk of high value ECT claims is a serious consideration when States debate regulatory change. A coordinated withdrawal should encourage State respondents to instead commit resources towards achieving agreed climate goals. One example is the Netherlands, which was required to pay roughly USD 355 million to two German energy suppliers that had initiated claims on the basis of the ECT (RWE v. Netherlands and Uniper v. Netherlands), when those funds could have been allocated towards implementing the country’s coal-exit policy. A similar trend is evident in more recent case law; see, for example, the decision in GreenX Metals v. Poland (I) and (II) summarised by the IISD, which concludes that, to this day, “the ECT’s ISDS mechanism enables foreign investors from the fossil fuel sector to challenge and seek compensation for public policy shifts”.

Addressing the Sunset Clause (Article 47.3) and Its Implications

Third, there are mechanisms available that limit the impact of clause 47.3 of the ECT, a “sunset clause“ that extends the protection of existing investments for a period of 20 years following a State’s withdrawal from the ECT (though importantly, this does not apply where there is a coordinated withdrawal).

The sunset clause protects older energy-intensive hydrocarbon investments whilst new investments based on cleaner, renewable energy sources will not be covered by the same protections and are therefore discouraged.

To minimise the risk of post-withdrawal claims, some States have sought to rely on the decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union in The Slovak Republic v. Achmea B.V. (Case C-284/16) and Moldova v. Komstroy (Case C‑741/19), which held that the ECT’s dispute resolution mechanism is incompatible with EU law. On 26 June 2024, the EU and its Member States reiterated this position by signing the “Declaration on the Legal Consequences of the Judgment of the Court of Justice in Komstroy and Common Understanding on the Non-Applicability of Article 26 of the Energy Charter Treaty as a Basis for Intra-EU Arbitration Proceedings“.

Further, the European Commission indicated that a subsequent agreement would be entered into following the coordinated withdrawal confirming “that the ECT cannot serve as a basis for arbitration proceedings, and that the sunset clause does not apply“.

In August 2024, the IISD published a “Model Inter Se Agreement to Neutralize the Survival Clause of the Energy Charter Treaty Between the EU and Other non-EU Contracting Parties“, designed to facilitate the negotiation of an inter se agreement that addresses the consequences of the sunset clause.

Addressing the Gaps: What Comes Next?

States must agree practical next steps to plug the lacuna that will undoubtedly arise from the withdrawal from the ECT, including in respect of renewable energy investments, which formed the bulk of claims brought under the ECT, both in terms of damages claimed and damages awarded.

One option is for States to consider the adoption and/or revision of Bilateral Investment Treaties (“BITs“) as opposed to the multi-lateral ECT; BITs can be tailored to better suit the intricacies of each State in question rather than adopting a one-size fits all solution.

In Africa alone, there were 525 BITs in operation as of October 2022, many of which do not expressly address standards of protection afforded to energy related investments. Incorporating investment protections aligned with the Paris Agreement (to which 80% of African countries are signatories) is particularly key given that:

- Countries across the African continent, and in the Global South generally, are considered to be some of the most vulnerable to the effects of climate-based dispute resolution; and

- A large portion of natural resources in Africa are owned by local governments such that changes in legislation or regulation that impact international investments in that sector will likely expose local governments disproportionately to investor-State claims.

According to a report published by Corporate Europe Observatory in December 2020, proponents of the ECT are said to have been “silently” promoting the ECT across the African continent: Burundi, Eswatini and Mauritania were at the ratification stage; Uganda was waiting for the formal invitation to accede to the ECT; and Niger, Chad, Gambia, Nigeria, and Senegal were in the process of preparing accession reports.

In light of the European exodus from the ECT, it may be preferable for African countries to instead review existing BITs and consider new draft BITs, such as the African Arbitration Academy’s Model Bilateral Investment Treaty for African States (2022), which seeks to strike a balance between attracting foreign investment and promoting sustainable development (e.g., Article 17(1)). This is similarly important for countries globally, including the UK, for whom securing supportive and progressive BITs is key to retaining the status of attractive and sustainable development hubs that support the energy transition. Unconditional investment protection should not be automatic nor constitute best international legal practice. States should be enabled to steadily amend environmental regulation and legislation, in line with international targets, with sufficient notice and protections for investors which allow them to adapt to the energy transition.

Another option is to encourage private insurance for investors to cover the risk of any changes in environmental regulations and/or legislations, as is commonplace domestically to cover business risks. In the international investment landscape, such risks are absorbed by Governments in treaties and statues. It is unclear whether there is any appetite on the part of private insurers to cover such investment risks, but clearer statutory regulation may encourage insurers to bear the brunt of and benefit from the economic risks of qualifying international investments.

Finally, the ECT, and many BITs, provide for an unqualified acceptance by States to agree to arbitration to resolve climate-focused disputes. However, there is scope to introduce an International Court for the Environment, adopted through contract or regulation and comprising of specialists who can implement procedures and resolve climate-related disputes. Whilst the concept is in its infancy, an International Court for the Environment has the potential to provide faster and more balanced solutions to international disputes than existing mechanisms.

Conclusion

Undeniably, the ECT in its current format is not fit for modern energy investments. This explains the mass withdrawal by several States, the EU’s coordinated withdrawal, and (the authors hope) the halt on various African countries’ accession to the ECT, all of which this article considers to be steps in the right direction.

However, the political clamour involved in engaging in a comparable multi-lateral treaty is equally undesirable. It is recommended that States look instead to support progressive and flexible BITs, which enable State sovereignty with sufficient investor security to encourage investment in clean and renewable energy. Other creative solutions include encouraging private insurance policies and the establishment of an International Court for the Environment. Time will tell which of these (if any) is preferred by the stakeholders involved in the energy transition.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Isabelle Wenger is an associate in Stephenson Harwood‘s international arbitration team. Since qualifying two years ago, Isabelle has been involved in several high-value and complex arbitrations, including Africa- and Middle East-related disputes. She also has a particular interest in investment treaty disputes and has contributed to Volume 19 of the ICSID Reports and the London VYAP – Daily Jus‘s blog post on “Recent trends in ICSID arbitration“, amongst others. Isabelle is also an unregistered barrister and was called to the Bar of England and Wales in 2019.

Ellen Dixon is an associate in the international arbitration team within Stephenson Harwood‘s commercial litigation department, regularly assisting clients with complex international commercial arbitrations across a variety of jurisdictions. In particular, her practice frequently involves disputes which are focused in Africa and Asia. Ellen has assisted clients with disputes governed by the LCIA, ICC, LMAA and GAFTA rules of arbitration as well as ad hoc arbitrations.

*The views and opinions expressed by authors are theirs and do not necessarily reflect those of their organizations, employers, or Daily Jus, Jus Mundi, or Jus Connect.