THE AUTHORS:

Timur Bondaryev, Managing & Founding Partner, Arzinger Law Firm

Volodymyr Nakonechnyi, Managing Associate, Arzinger Law Firm

Anastasiia Kotliarchuk, Associate, Arzinger Law Firm

Since 2014, Ukraine has been sustainably employing various multifaceted and creative legal strategies to recover the damages, caused by Russian aggression and increase pressure on Russia and its allies and supporters.

Many Ukrainian private individuals, businesses, and state-owned companies have been evaluating their options for investment disputes against Russia.

However, Ukraine could soon face its own challenges and, possibly, even investment claims arising from its new sanctions-related initiatives, which stem from the legislature and, surprisingly, the judiciary.

As a starting point, one shall understand that the current Law of Ukraine on Sanctions allows both freezing and, at a later stage, appropriation of frozen assets in the court proceedings initiated by the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine (“MoJ”).

The current mechanism for sanctions enforcement and collecting the assets by the State of Ukraine has functioned relatively well. However, there is only a limited amount of “tangible” Russian assets in Ukraine, directly or indirectly (through the companies which serve as a holding vehicle) owned by sanctioned individuals, which may be subject to sanctions-based appropriation.

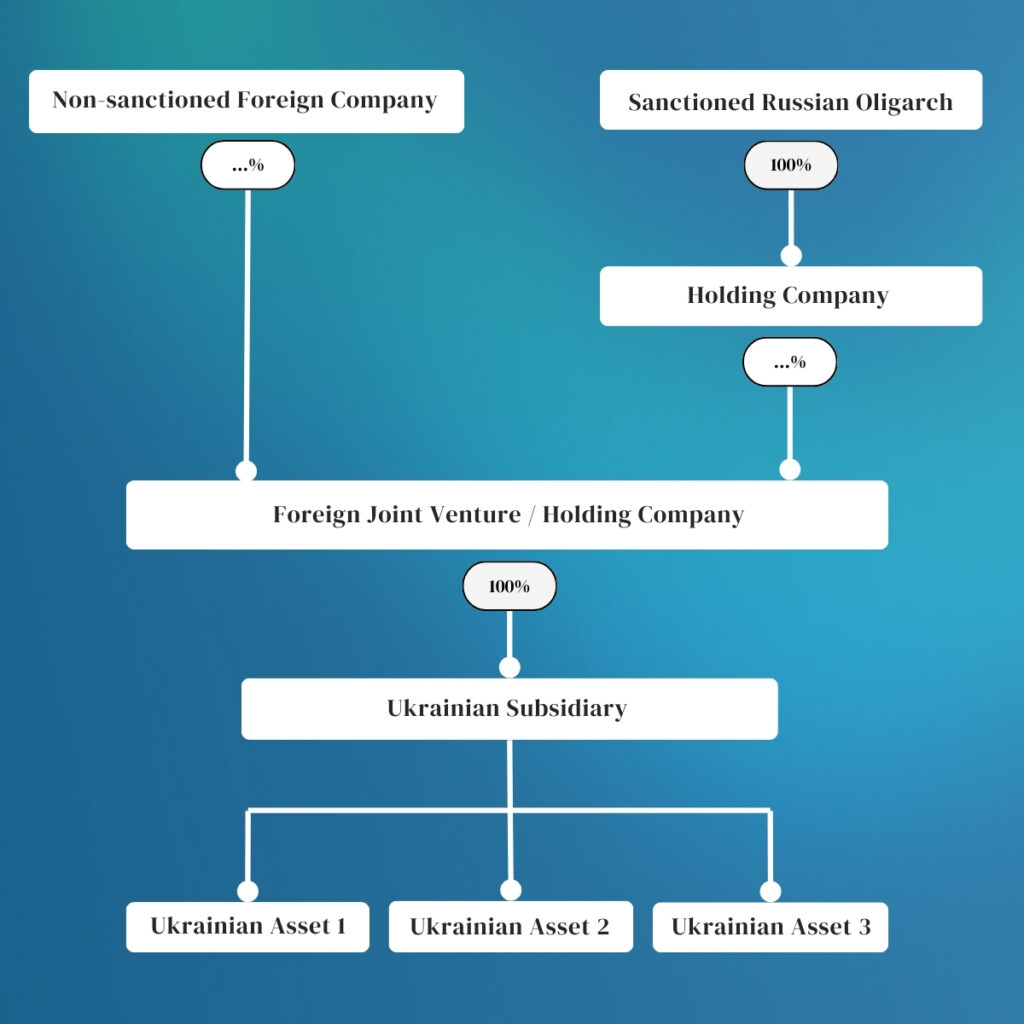

Most often the assets of significant value are held by a Ukrainian subsidiary of a foreign company with a sophisticated multi-level ownership structure in foreign jurisdictions, where one of the UBOs might be a sanctioned Russian oligarch, while another one is a reputable and non-sanctioned foreign investor protected by several investment treaties. This can be well illustrated by the following scheme:

While it is a rather usual structuring approach to shielding the assets of [sanctioned] entities and individuals, Ukraine decided to resolve this issue in a somewhat surprising manner – by allowing to collect the assets, indirectly held by the non-sanctioned investors.

The origins of this idea, subsequently re-introduced in notorious Draft Bill No. 11195, could be traced to the case of Shell, where the assets of non-sanctioned foreign investors were first collected. While the Bill was subsequently abolished, the representatives of the Ukrainian Government made it sufficiently clear that after polishing the technicalities, the main concepts and ideas will most definitely resurface in a new legislative initiative.

The Case of Shell

Disclaimer: The authors represented Shell in legal proceedings before the courts of Ukraine. In any event, the conclusions offered in this article reflect our true professional opinion.

All information regarding the case below is available in the public domain, in particular, in publicly available court decisions.

Shell entered the Ukrainian market long ago, acting as a JV – partner in a Dutch joint venture (JV), which in its turn has been owning Ukrainian assets and running Ukrainian business. Shell was a majority shareholder with 51% of shares in the JV, while the Russian oligarch Khudainatov held 49% shares in the JV.

Following the full-fledged Russian invasion into Ukraine in February 2022, Shell’s JV partner, as a number of other Russia-linked businesses & individuals, was sanctioned by various jurisdictions (including Ukraine).

The sanctions have entitled Ukraine to nationalization of the assets, owned by the sanctioned person and the respective claim was submitted by MoJ to the High Anticorruption Court of Ukraine.

MoJ asked the court to nationalize the Ukrainian assets of the sanctioned person, which, as a matter of fact, constituted the assets, indirectly (through the JV) belonging to Shell. In fact, Ukraine has claimed nationalization of the assets, which didn’t really belong to the sanctioned person but was owned by a reputable international investor.

In October 2023, Shell suddenly found itself in the middle of a legal dilemma. Ukrainian claims to 49% of shares in the Ukrainian subsidiary directly held by the JV, allegedly linked to Khudainatov, raised a critical issue: what happens when third-party assets are caught in the net because one of the indirect minority shareholders is sanctioned?

Disclaimer: While the dispute involved multiple legal issues apart from the legality of taking the assets of non-sanctioned JV (and indirectly Shell), we intentionally refrain from discussing these separate issues to keep this article simple and concise. One of such issues deals with the effects of dilution (issue of new shares for the benefit of Shell) at the JV level, which allowed Shell to increase its stake in JV to 97,44%. Therefore, another important aspect of the Shell case was dealing with the allocation of shares and what stake in the JV was actually owned by the sanctioned entity.

The High Anticorruption Court, as the court of first instance, resolved the case in accordance with the current laws and in line with the international obligations of Ukraine, rejecting the claims of the MoJ to the assets owned by non-sanctioned entities – the JV and, indirectly, by Shell.

The Appeal Chamber, however, reversed the judgment and ruled to seize 100 % of the Ukrainian subsidiary of JV, effectively depriving the Dutch JV Cicerone of all its possessions. The Appeal Chamber allowed Shell to subsequently re-register 51% of shares in the name of Shell, while the remaining 49%, previously directly owned by the non-sanctioned JV, were appropriated by the state.

Draft Law on Enforcement Against the Third-Party Assets

After the case of Shell had been resolved in the interest of the State of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Parliament decided to set in stone the logic employed by the Appeal Chamber and allow applying it in similar cases in the future, notwithstanding the very foreseeable risks.

MPs have put forward a Draft Bill No. 11195, that would allow the courts to enforce sanctions by collecting the assets owned not only by the sanctioned individuals, but also by non-sanctioned third parties. Ukrainian lawmakers clearly have a good sense of humour, as they decided to name this bill “On the Mechanism for the Protection of Third-Party Rights”.

The Bill envisaged that court-ordered enforcement could affect any third party, which holds assets in Ukraine if a sanctioned party holds indirectly 25 + % interest in such assets. If the stake of the non-sanctioned party is lower than 25 %, the situation is even worse – the powers to collect such assets for some reason are awarded to the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, the highest executive body, which acquires unlimited discretion to decide whether the foreign investor gets to keep their property, omitting all and any standards of fair trial.

In fact, the Draft Bill entitled/required the non-sanctioned indirect shareholders – partners with sanctioned persons, to directly apply to Ukraine to register their ownership interest in Ukrainian assets in Ukrainian domestic registers. Obviously, this approach raises a number of practical implications for investors.

For example, it seems very unlikely, that the investors, who purchased shares of a public company, listed, for instance, at NASDAQ and having Ukrainian business, will be happy to re-register their ownership rights in Ukraine, due to the fact, that there is a sanctioned investor among the shareholders of the company.

The practice of seizing assets without a direct link to sanctioned individuals isn’t just a legal novelty; it is a potential minefield.

Given the high pressure of civil society, the MPs withdrew the Bill from consideration. It is a local victory, but the State does not seem to abandon the idea of collecting assets owned through complicated foreign corporate structures. We expect that a new Bill will be presented soon, and the question remains open – will Ukraine be able to properly balance the rights of bona fide foreign investors and its own desire to seize assets? If the response to this question is negative, Ukraine may find itself facing multiple claims of expropriation.

The Prospects of Investment Claims against Ukraine

While there is no doubt that a sovereign is entitled to introduce and enforce sanctions to protect its national interests, no such measures must lead to the outright expropriation of the assets owned by the non-sanctioned parties. Foreign investors are likely to use an investment protection shield against unlawful expropriations, turning to the arbitration under the applicable BITs.

If such disputes arise, jurisdictional and admissibility defenses with reference to the principles of transnational public policy and the doctrine of clean hands, which may be used by the state in ordinary sanctions-related cases, will be useless when the enforcement of sanctions results in the taking of property owned by non-sanctioned investors.

As to the merits, judicial expropriations from non-sanctioned investors would hardly meet the customary criteria of non-discrimination, proportionality and due process. The legitimate purpose for taking non-sanctioned assets also raises significant concerns.

On a case-by-case basis, the investor may also turn to the non-discrimination and FET clauses. For example, affected investors may assert they faced discriminatory treatment because they lost a significant portion of their assets in prolonged lawsuits and appropriations.

At the same time, in the most recent case, investors in a large Ukrainian telecom company with sanctioned individuals in its corporate structure, have cleared their exit with the Ukrainian competition authority and sold Ukrainian business to an international investor, effectively eliminating any risks of lawsuits and appropriation. This can hardly be considered equal treatment in very similar circumstances.

Conclusion

Legal and reputational stakes are high in any case concerning sanctions.

Ukraine is understandably exploring all available avenues to keep the resistance going against the Russian invasion. However, further aggressive measures could inadvertently scare off bona fide foreign investors, potentially doing more harm than good in the long run.

This story of sanctions, asset seizures, and potential expropriation is also a reminder of how politicized and complex the sanctions process can become. As Ukrainian lawmakers deliberate whether it is worth to formalize flawed practices for the sake of effective access to previously unreachable assets, they should proceed carefully. Balancing the need to enforce sanctions with the obligation to maintain a stable investment climate is quite a challenge, and the outcome will shape Ukrainian legal landscape as well as the future of Ukrainian economy.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Timur Bondaryev is a Founding & Managing Partner at Arzinger Law Firm, Attorney-at-Law, Head of Cross-Border Litigation & Arbitration Practice, Co-Head of Antitrust and Competition Practice. Timur is a respected lawyer with an exceptional reputation and more than 20 years of professional experience in the Ukrainian and international markets. He has extensive experience in commercial and investment arbitration under the rules of various major arbitral institutions worldwide, as well as UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. Timur also specializes in supporting complex transactions and antitrust investigations in Ukraine and abroad with the participation of international and national investors. Timur’s expertise has been recognized for many years by leading international ratings, including Chambers, Legal 500, etc.

Volodymyr Nakonechnyi is a Managing Associate of Cross-Border Litigation & Arbitration Practice at Arzinger Law Firm, Attorney-at-Law. Volodymyr has more than 9 years of professional experience. He particularly focuses on the investment arbitration sphere and negotiations with the state on the settlement of investment disputes. He represented foreign investors in investment disputes in cases Gilead Sciences Inc. v. Ukraine, Philip Morris v. Ukraine, and Morgan Furniture v. Ukraine, settled peacefully during the cooling-off period. Volodymyr also represented clients in commercial arbitration and advised clients on disputes under the rules of key arbitral institutions (LCIA, SCC, SAC, VIAC, ICAC, GAFTA, FOSFA). He advised clients on complex cross-border dispute strategies, the enforcement of arbitration awards, and foreign court decisions in different jurisdictions.

Anastasiia Kotliarchuk is an Associate of Cross-Border Litigation & Arbitration Practice at Arzinger Law Firm, Attorney-at-Law. Anastasiia has over 5 years of professional experience in investment and commercial arbitration, as well as litigation. She represented foreign investors in investment disputes in Philip Morris v. Ukraine, Morgan Furniture v. Ukraine, and related national court proceedings. Anastasiia has also represented clients in commercial arbitration and advised on disputes under the rules of key arbitral institutions (LCIA, SCC, SAC, VIAC, ICAC, GAFTA, FOSFA).

*The views and opinions expressed by authors are theirs and do not necessarily reflect those of their organizations, employers, or Daily Jus, Jus Mundi, or Jus Connect.