THE AUTHORS:

Tushar Behl, International Dispute Resolution Lawyer

Liana Cercel, International Dispute Resolution Lawyer

Introduction

A new global economic focus on tackling climate change has arisen: shift to a net-zero economy. Investors are now accounting for Environmental Social Governance (“ESG”) risks and costs in their investment strategy. This transition has generated two key effects. On one hand, the re-evaluation of investments resulted in green projects gaining value due to their lower projected compliance risk. On the other hand, the phasing out of fossil fuel and non-compliant investments being triggered, by radically changing the economic circumstances at the time of investment. Both perspectives are projected to generate considerable disputes in the coming decades.

General Matrix of Climate Change Disputes

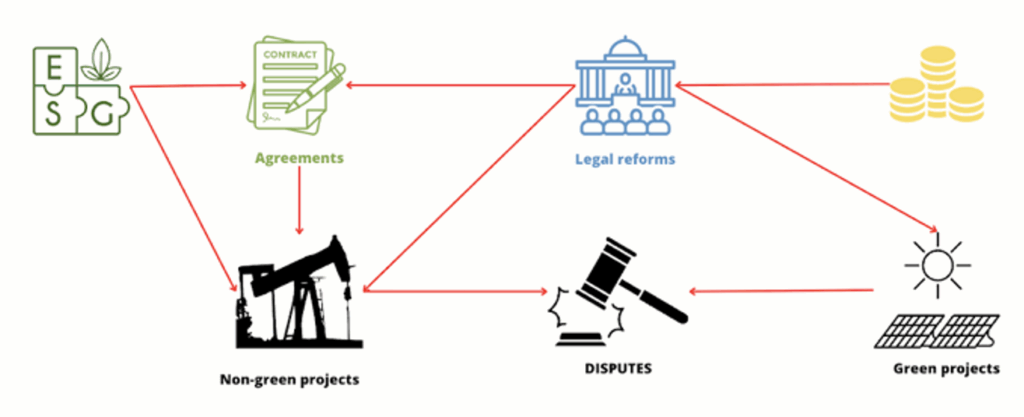

There is no universally accepted definition of climate change disputes in international arbitration. In the global transition towards a net-zero economy, any dispute could be a climate change dispute. Modern climate change disputes thus emerge not as a distinct category, but from a complex interplay of regulatory frameworks at the national and international level; contractual obligations; financial considerations and commercial factors that reflect the global transition to sustainability. This interplay (or ‘matrix’) creates dynamic tensions between traditional and renewable energy investments, while ESG considerations increasingly influence both contractual frameworks and project development. The matrix depicted below illustrates the complex interplay between key actors and factors in climate change disputes. ESG considerations and environmentally-driven legal reforms serve as primary drivers, influencing both contractual frameworks and project development across the energy sector. Financial flows demonstrate the market’s dual response: funding green projects while influencing regulatory changes that affect traditional investments. This creates a dynamic where disputes can arise from multiple sources: the phase-out of non-green projects, the development of green projects and the regulatory transitions.

The matrix thus captures how modern climate change disputes emerge not from isolated events, but from the dynamic interaction between ESG requirements, contractual obligations, regulatory frameworks and financial imperatives across both traditional and renewable energy sectors. These interconnected relationships explain why arbitration has emerged as the preferred dispute resolution mechanism. The matrix must accommodate ESG requirements, contractual obligations, regulatory changes and financial considerations while balancing the interests of multiple stakeholders across jurisdictions. This complexity is reflected in both commercial arbitration cases (dealing primarily with contractual and ESG compliance issues) and investment arbitration cases (addressing regulatory changes and state measures).

ESG-Centric Regulatory Shift

ESG demands indeed introduce new risks to projects, particularly in terms of compliance, reputational damage and potential disputes with stakeholders. These risks often arise from increased scrutiny of sustainability practices, climate-related goals and the need for socially responsible corporate behavior. The primary significant risk is the growing pressure on companies to meet international climate agreements, which can lead to friction between local regulations and global sustainability standards. In industries such as energy, new technologies, and market entrants can also cause disputes due to regulatory uncertainties and the complexities of scaling operations sustainably.

As a prime example of this ESG-centric shift, consider the International Chamber of Commerce’s Institute of World Business Law joint project with UNIDROIT. The UNIDROIT Principles and International Investment Contracts (“IICs”) project aims at developing guidance to foster the modernisation and standardisation of IICs. It will explore the interaction between the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts and common provisions in IICs, and it will seek to address a number of recent developments in the area of International Investment Law (“IIL”), including Sustainability, ESG and Corporate Responsibility obligations. A further good example is that the World Bank adopted a strict Environmental and Social framework which includes adding strict conditions on environmental and social requirements to all contracts by the World Bank. This applies to, e.g., all FIDIC contracts for construction projects.

Overall, there are two types of project-specific actions that could incur additional risks and, most relevant, costs:

- Remediation (i.e., positive actions the project enables to counter climate impact);

- Decommissioning (i.e., negative measures the project must take to reduce emissions).

Accounting for environmental impact has also changed the ‘investment equation’ by introducing ESG risks.

ESG-Centric Regulatory Shift Reshaping Arbitration

The net-zero regulatory shift has led to a rise of climate change disputes or, rather, climate change related issues being addressed in international arbitration. The construction of energy infrastructure and the provision of equipment (including supply chain) caused the most international energy disputes in the past five years and will cause the most international energy disputes in the next years. Proof of that can be found in the ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics. As of 2023, the construction and energy industries accounted for nearly half (cca. 45%) of all new ICC cases registered last year, making them the industries that generated the largest number of cases. This is consistent with previous years, where the construction and energy sectors generated 45% of new cases in 2022 and 44% of new cases in 2021.

This regulatory shift emphasizing ESG compliance is marked by the rise of renewable energy-related arbitrations, evolving dispute resolution mechanisms, and reforms to support energy transitions, such as the development of critical infrastructure and legal protections. Two key way:

- International arbitration is increasingly preferred as a mechanism for resolving ESG-related disputes; and

- There is a proven increase of energy-related arbitrations, specifically in the construction industry related to energy infrastructure.

Legislative frameworks now emphasize the role of arbitration in resolving disputes arising from new technologies, supply chain issues, and energy decommissioning, reflecting the broader goals of achieving sustainability and mitigating climate-related risks.

Over the last two decades, climate change governance has manifested through various regulatory instruments spanning international, regional, national and sub-national scales. Three primary international agreements regulate state-level climate change actions:

- First, the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (“UNFCCC”), an international collaborative effort to counter climate change by stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions, limiting average temperature increases and their resulting environmental repercussions;

- Second, the 1998 Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, enacted to bind signatories in meeting carbon emission reduction targets; and

- Third, the 2015 Paris Agreement, striving to limit global temperature rise to 2°C above pre-industrial levels with additional efforts to cap global warming at 1.5°C.

While both, the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement offer recourse to inter-state arbitration based on submission agreements, the offered regimes, however, have had little chance of materializing. Climate-related investment disputes are routinely brought by foreign investors against host states by resorting to the ISDS mechanism primarily under the relevant BITs, multilateral investment treaties or investment chapters of Free Trade Agreements.

To resolve the tension between IIL and climate goals emerging from climate-related disputes, the ‘reformist approach’ underscores the need and potential of substantial and procedural reforms under IIL to reconcile the protection of climate-affiliated investments and the expansion of states’ regulatory space. While substantive reforms require reconsideration of the way in which International Investment Agreements (“IIAs”) provide investment protection in the climate sector, procedural reforms require adjudication mechanisms to carefully account for climate considerations.

Various contemporary agreements, such as the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, include provisions that support investments in climate-sensitive sectors. For example, they promote and facilitate investment relevant to climate change mitigation and adaptation as defined in Section IV, Article 6. These agreements are typical examples of substantial reforms, aimed at enhancing the host states’ regulatory space. The Agreement in Principle on the Modernization of the Energy Charter Treaty (“ECT”) provides for similar wording in that regard.

Several Model BITs have been updated to include reforms of these standards, such as the express reference of the Paris Agreement in Article 6(6) of the 2019 Netherlands Model BIT and the 2021 Canada’s Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement specifying six exclusive circumstances through which a breach of the Minimum Standard of Treatment can be established departing from the erstwhile ‘unqualified’ FET approach.

States vary in their approach in incorporating environmental provisions in treaties, however a general structure of obligations is prevalent: Preambles of IIAs increasingly tend to mention, in their object and purpose as general goals shared by the contracting parties, ‘sustainable development’ and/or ‘environmental protection’, for example Argentina – UAE BIT (2018) and Argentina – Japan BIT (2018). Others grant broader discretion to states to determine their own level of environmental protection with carve-out clauses balancing investment protection and environmental safeguards, for example Canada – China BIT (2012) and Canada – Slovak Republic BIT (2010). Some treaties incorporate soft law and guidelines by incorporating provisions on Corporate Social Responsibility (“CSR”), for example, Brazil – Mozambique CFIA (2015) and Benin – Canada BIT (2013). Some states reaffirm their obligations while incorporating specific provisions on environmental protection, for example Art. 10 of the Colombia – UAE BIT (2017), Annex B(3)(b) of the Australia – Uruguay BIT (2019) and Article(s) 15,18, 21, 30 and Annex I (3)(b) of the Chile – Hong Kong, China SAR Investment Agreement (2016).

Within the international law framework, among multilateral agreements that blend environmental obligations and investment protection with the ability to resolve disputes through arbitration, three significant examples emerge:

- The 2016 Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (“CETA”) between the EU and Canada. The CETA includes robust environmental protection provisions under Chapter 24 on Trade and Environment committing to high levels of environmental protection, sustainable development and enforcement of domestic environmental laws. Within the context of Chapter 8, i.e. the investment protection chapter, a draft interpretative statement released by the CETA Joint Committee on February 9, 2024, covers climate change as one of its main areas and affirms that the tribunal must accord due consideration of the climate neutrality objectives and commitments made by parties to the Paris Agreement while interpreting the provisions of Chapter 8. CETA also provides for an Investment Court System (“ICS”), enabling investors to resolve investment disputes with host states transparently and with an opportunity for appeal, balancing environmental obligations and investor rights.

- Second, the 2018 United States – Mexico – Canada Agreement (“USMCA”), the successor of the North American Free Trade Agreement, providing for Chapter 24 exclusively dedicated to environmental conservation and regulatory enforcement; encompassing comprehensive environmental protection provisions coupled with parties’ autonomous right and authority to determine their domestic environmental standards; prescribing protocols for enforcement of environmental law and specifying principles governing commercial conduct and CSR responsibility under Chapter 14.

- Third, the 2018 Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (“CPTPP”) incorporates comprehensive environmental protection provisions. Chapter 20 commits all member countries to uphold and enforce their domestic environmental laws, promote sustainable development and attempts to avoid enfeeble environmental protections to attract trade and/or investment. This includes commitments on a variety of issues such as biodiversity, marine conservation, climate change and illegal wildlife trade.The CPTPP also retains the ISDS mechanism from its predecessor, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (“TPP”), although some provisions have been suspended or modified in the CPTPP.

In fact, several trade agreements signed by the European Union incorporate both environmental obligations and provisions for Investor-State Dispute Settlement (“ISDS”), similar to CETA. Here are some key examples:

- 2018 EU-Singapore Free Trade Agreement (“EUSFTA”): This agreement includes commitments to sustainable development, environmental protection, and climate action under its Trade and Sustainable Development Chapter. It also provides for ISDS mechanisms, allowing for arbitration in disputes between investors and the state under certain conditions.

- 2019 EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (“EVFTA”): The EVFTA incorporates strong environmental protections in its Sustainable Development Chapter, which covers issues like biodiversity, climate change, and sustainable forest management. It also includes ISDS mechanisms through its investment protection agreement, allowing investors to use arbitration to resolve disputes.

- 2018 EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (“EPA”): While the EU-Japan EPA has a robust Sustainability Chapter addressing environmental issues, it does not include an ISDS mechanism. However, it features state-to-state dispute resolution and commits to future discussions on investment protection, potentially involving arbitration.

- EU-Mexico Global Agreement: The updated version of the EU-Mexico Global Agreement includes comprehensive environmental obligations and ISDS provisions. The modernized agreement strengthens cooperation on climate action and sustainable development while allowing investors to use arbitration under certain circumstances.

- EU-Mercosur Agreement: This agreement, once ratified, will include commitments to environmental protection, sustainable development, and climate change. It is expected to have ISDS mechanisms similar to CETA, offering arbitration as a method to resolve disputes related to investments.

These agreements reflect the EU’s broader approach of combining environmental obligations with investment protection, often allowing arbitration as a dispute resolution mechanism.

Arbitration as the Preferred Forum for Climate Change Disputes

Arbitration provides security for energy and other sector investments by offering a reliable dispute resolution mechanism that investors can trust when committing significant capital to projects, especially in a different jurisdiction to their own. It has also proven to be one of the most efficient legal tools in managing complex, multi-party, multi-contract initiatives involving multiple jurisdictions. For example, regional power grid integration typically involves cross-border infrastructure, with several states and other actors collaborating, also for supply and distribution. Two notable examples include, the North Seas Energy Cooperation (“NSEC“), where EU member states collaborate on offshore wind power projects and grid connections in the North Sea, Irish Sea, and Celtic Sea and the European Network of Transmission System Operators (“ENTSO-E“), a consortium of 40 energy operators across Europe which coordinates the interconnection and operation of electricity grids across Europe. Arbitration provides a unified dispute resolution mechanism that all parties can agree on, rather than navigating multiple national court systems.

Disputes related to the energy transition and climate-related issues are likely to continue increasing rapidly in all cases. Statistically confirmed, 72% of end users prefer the use of arbitration to resolve energy disputes on account of expertise, neutrality, efficiency, flexibility and recently the ‘greener’ initiatives and practices adopted by institutions to reduce environmental impact, such as virtual hearings, electronic document management, paperless submissions, etc.

The combination of the aforementioned factors – neutrality, expertise, efficiency and flexibility make arbitration particularly well-suited to handle both current and emerging climate-related disputes. This is reflected in the significant proportion of energy disputes in both major arbitration institutions: 17.3% of ICC cases and 44% of ICSID cases in 2023. The recent increase in ICC energy disputes, up by 3.1 percentage points from 2022, suggests growing reliance on arbitration across multiple sectors, from traditional energy and construction to specialized technologies and financial services. This comprehensive dispute resolution framework supports the global transition to a net-zero economy while maintaining the necessary balance between investor protection and states’ regulatory powers.

Conclusion

Legislated ESG frameworks as discussed in detail above, tend to inspire greater investor confidence, as they are backed by government enforcement and standardized disclosures. Investors can rely on consistent, verified data that adheres to regulatory requirements. Guidelines, while influential, are often seen as less reliable. Investors may question the rigor of voluntary compliance, making them less confident in the accuracy or thoroughness of ESG reports based solely on guidelines. In conclusion, ESG demands based on legislation offer stronger enforceability, standardization, uniformity and investor trust but can be less flexible, while guiding principles and guidelines allow for adaptability but may suffer from inconsistencies and weaker enforcement mechanisms. Both have their advantages, but legislative backing tends to drive more systemic change in corporate behavior.

It also remains to be seen how these newer-generation IIAs containing safeguards to the host state’s right to regulate (carve outs, re-affirming and general exception clauses) are interpreted by investment tribunals since investment treaty and ECT proponents advocate for the role of investor protections for renewables as an attempt to preserve the existing investment regime in the face of shattering public trust. It is worthy to understand that investors do face significant constraints while investing in green and renewable energy projects. The older generation IIAs are not able to attract these investments and meanwhile, states expose themselves to potential liability due to the very dynamic and responsive nature of their regulations required for energy transition. The question remains, while arbitration is still the preferred means, should states desirous of achieving their climate change goals consider withdrawing from their IIAs in order to maintain the necessary regulatory and policy space to implement climate change policies?

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Tushar Behl, ACIArb is an international dispute resolution lawyer, qualified in India, with an LL.M. in Transnational Arbitration and Dispute Settlement from Sciences Po Law School, Paris.

Liana Cercel, is an international lawyer admitted to the New York and Bucharest Bar, practicing as an Independent Counsel within the Brigantia Law network and part of the LL.M. in Transnational Arbitration and Dispute Settlement program at Sciences Po Law School, Paris.

*The views and opinions expressed by authors are theirs and do not necessarily reflect those of their organizations, employers, or Daily Jus, Jus Mundi, or Jus Connect.