This article was featured in our 2023 Construction Arbitration Report, which is part of a series of industry-focused arbitration reports edited by Jus Connect and Jus Mundi.

This issue explores the construction industry and presents a goldmine of information based on data available on Jus Mundi and Jus Connect as of May 2023. Discover updated insights into construction arbitration and exclusive statistics & rankings, as well as in-depth global and regional perspectives on construction projects, disputes, & arbitration from leading lawyers, arbitrators, experts, arbitral institutions, and in-house counsel.

THE AUTHORS:

Diora Ziyaeva, Partner at Dentons

Dogan Eymirlioglu, Partner at BASEAK (Dentons local partnership)

Over the past two decades, Türkiye, in addition to Central Asia as a whole and the Middle East and North Africa (“MENA”) region, has seen an influx in investment arbitration relating to cross-borders construction projects. This article will analyze the trends apparent in these investment arbitrations, as well as provide guidance to investors in the regions.

General Trends

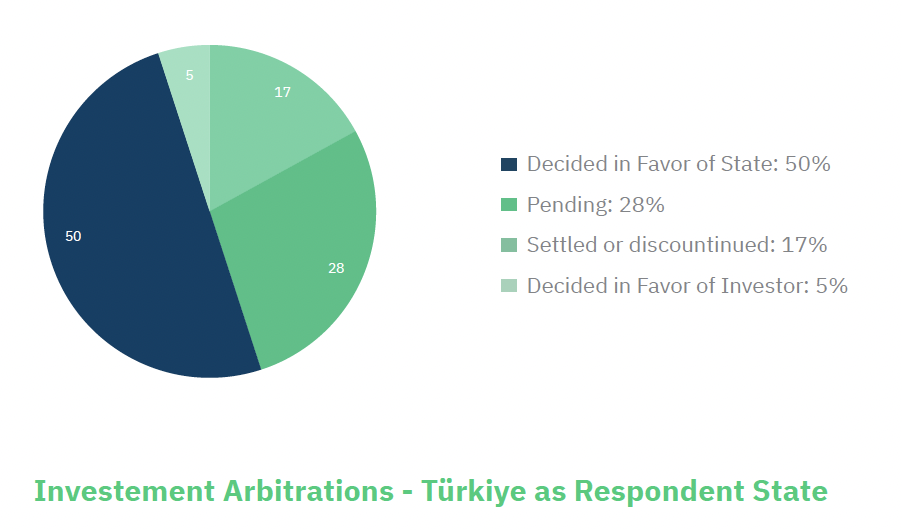

To understand the trends in investment arbitration in Türkiye, and more broadly throughout the Central Asian and MENA regions, it is important to examine the types of disputes being brought and the relevant countries involved. Türkiye has itself been a Respondent in eighteen investment arbitrations.

Out of the thirteen cases that have concluded, nine were decided in favor of the State, one decided in favor of the investor, and three settled or dis- continued. There have been four cases involving construction projects in which Türkiye was the Respondent, arising out of the: (1) Turkey-United States BIT; (2) Energy Charter Treaty; (3) Netherlands-Turkey BIT; and (4) Austria-Turkey BIT.

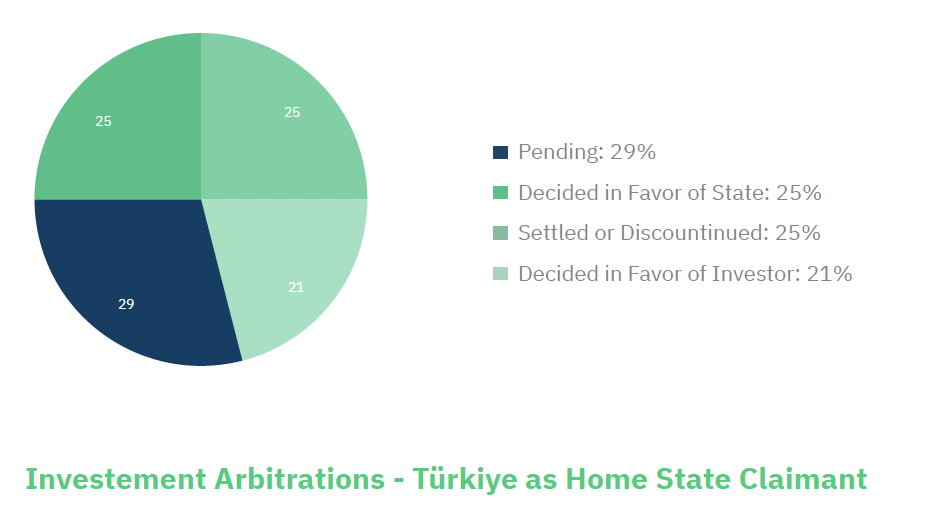

Türkiye has been the home state of the Claimant in forty-eight investment arbitrations.

Of the thirty-four cases that have concluded, twelve were decided in favor of the State, ten decided in favor of the investor, and twelve settled or discontinued. Nearly half of these cases – twenty in total – involved construction projects. Similarly, Turkish companies have brought investment arbitrations against a number of states.

The construction-specific cases in which Turkish investors were Claim- ants have arisen out of the: (1) Pakistan-Turkey BIT; (2) Libya-Turkey BIT; (3) OIC Investment Agreement; (4) Turkey-Turkmenistan BIT; (5) Saudi Arabia-Turkey BIT; (6) Azerbaijan-Turkey BIT; (7) Oman-Turkey BIT; (8) Jordan-Turkey BIT; and (9) Georgia-Turkey BIT.

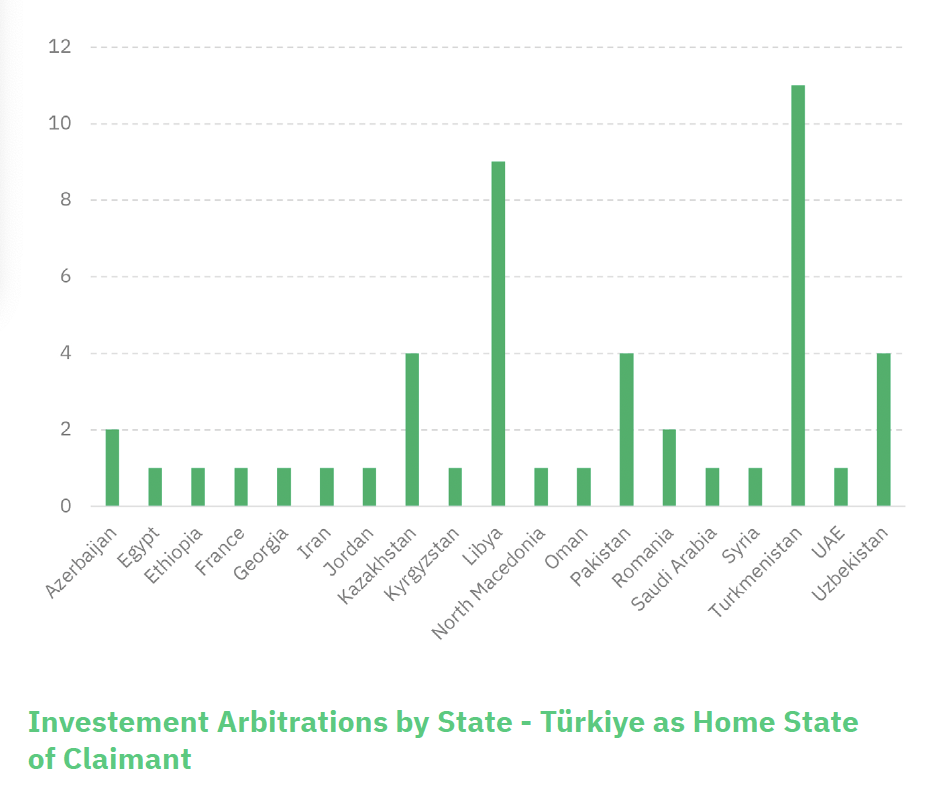

Turkmenistan has been the most common adversary in these proceed- ings, appearing as the Respondent State in at least nine arbitrations of construction disputes with Turkish investors to date. Libya has appeared as the Respondent state in multiple arbitrations of construction disputes with Turkish investors as well.

Likewise, other states in the Central Asian region have been involved in a number of investment arbitrations. Turkmenistan has been the Respon- dent state in sixteen investment arbitrations, the vast majority of which have involved construction projects. Kyrgyzstan has been the Respon- dent State in eighteen investment arbitrations, several of which involved construction projects. Kazakhstan has been the Respondent State in nineteen investment arbitrations while it has also been the home State of the Claimant in six other investment arbitrations. Uzbekistan has been the Respondent State in nine investment arbitrations and the home State of the Claimant in one other. By contrast, Tajikistan has only been the Respondent State in two investment arbitrations, neither of which involving a construction project.

The Central Asian region is not alone in consistently utilizing investment arbitrations. Dozens more investment arbitrations have been initiated against or on behalf of States in the MENA region. In fact, the MENA region has represented roughly 19% of ICC cases filed in recent years – as well as 9% of recent ICSID cases. A number of these arbitrations have involved substantial awards. For example, a Spanish company prevailed before an ICSID tribunal on a $2 billion USD claim against Egypt in 2018 (See, Unión Fenosa Gas, S.A. v. Arab Republic of Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/4).

The increase in investment arbitration participation in Türkiye should come as no surprise as the State has consistently expanded its number of relevant treaties. Just in the last five years, Türkiye has signed an addi- tional eight bilateral investment treaties, in addition to free trade agree- ments with the U.K. and E.U.

- Türkiye-Uruguay BIT, signed in 2022 [not ratified]

- Democratic Republic of the Congo-Turkey BIT, signed in 2021

- Angola-Turkey BIT, signed in 2021

- Burkina Faso-Turkey BIT, signed in 2019

- Cambodia-Türkiye BIT, signed in 2018

- Turkey-State of Palestine BIT, signed in 2018

- Lithuania-Turkey BIT, signed in 2018

- Turkey-Zambia BIT, signed in 2018 and entered into force in 2020

For the Central Asian region, this increase in participation in investment arbitrations coincides with each State’s actions to develop an individual investor-state framework following the collapse of the USSR. As each State continues to develop as economic powers, the need for foreign investment –and with it protections for foreign investors – grows. In the MENA region, while overall levels of participation are strong, the explanation varies from State to State, including both an influx of signed BITs and the effects of events like the Arab Spring.

Noteworthy Cases

The uptick in arbitrations brought on behalf of Turkish construction com- panies began in the mid-2000s. In 2006, a Turkish construction company Sistem Muhendislik Insaat Sanayi ve Ticaret AS (“Sistem”) initiated an ICSID arbitration stemming from a hotel project in the Kyrgyz Republic (See, Sistem Mühendislik Inşaat Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş. v. Kyrgyz Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/06/1). The dispute dates back to a 1992 joint venture between Sistem and a Krygyz company to build and operate the Hotel Pinara in Bishkek. In 1999, due to the bankruptcy of the Krygyz company, Sistem purchased the full ownership share of the hotel and operated it until 2005. In March 2005, following a revolution in Kyrgyztan, Sistem’s staff members were physically removed from the hotel and barred from its operation by the former joint venture partner. Shortly thereafter, a local Kyrgyz court reversed the joint venture partner’s bankruptcy, and awarded the company the 50% share in the hotel that Sistem had previ- ously purchased. Even though under this scenario Sistem would also own a 50% share in the hotel, the investor was prevented from operating the hotel.

After unsuccessfully resorting to local courts to regain access to the hotel, Sistem brought claims under the Kyrgyzstan-Turkey BIT for expropriation and breach of the guarantee of full protection and security (“FPS”).

The tribunal agreed with Sistem on the expropriation, finding that the company was wrongly deprived of its interests in the hotel. While Sistem sought lost profits, the tribunal noted that the BIT’s expropriation provi- sion required compensation of the real value of the hotel at the time of the taking. Following expert submissions from both parties, the tribunal awarded $8.5 million USD, plus interest, to compensate for the expropri- ation. Finally, the tribunal declined to address the FPS claim, finding that Sistem had been fully compensated for the expropriation.

In recent years, two areas in particular have led to interesting developments in investment law in the two regions.

The first area of interest involves two recent arbitrations brought by Turk- ish companies against Turkmenistan – Kiliç v. Turkmenistan (ICSID Case No. ARB/10/1) and İçkale v. Turkmenistan (ICSID Case No. ARB/10/24). Each case dealt with the application of Article 7(2) of the BIT, which first requires the investor to resort to the local courts of the host State and how to address that provision in light of multiple, and conflicting, transla- tions. While each tribunal eventually held that only the English and Rus- sian versions of the BIT were authentic, they differed on how to handle disparities between the two versions.

In Kiliç, the Claimant alleged that Turkmenistan failed to pay certain amounts owing under various construction projects and sought damages of nearly $300 million USD for violations of the Turkey-Turkmenistan BIT. Likewise, in İçkale, the Claimant initiated ICSID arbitration under the Tur- key-Turkmenistan BIT stemming from various construction projects. The Claimant sought damages of roughly $570 million USD.

The Kiliç tribunal analyzed the translation issue under Article 33(4) of the VCLT and held that the whole of Article 33 reflects customary inter- national law. The tribunal then interpreted Article 7(2)’s requirement of first bringing claims in local courts as a matter of jurisdiction. The İçkale tribunal disagreed, holding that this requirement was not “a condition to Turkmenistan’s offer to submit itself to the jurisdiction of an international tribunal to arbitrate investor-State disputes under the Treaty.” Therefore, it was judged as a matter of admissibility instead, with the tribunal then dismissing the claims as contractual, instead of treaty-based.

A later tribunal dealing with annulment proceedings in Kiliç avoided the Article 7(2) issue entirely, focusing instead on Article 52 of the ICSID Con- vention. The tribunal’s decision demonstrates that re-interpretating Article 7(2) of the BIT is neither necessary to annul an award on the basis of Arti- cle 52 of the ICSID Convention nor related to the grounds for annulment.

The second area of interest involves arbitrations stemming from the dif- ficulties Turkish construction companies had in Libya following the 2011 civil war.

In 2016, a Turkish company Cengiz İnşaat Sanayi ve Ticaret A.S. (“Cen- giz”) initiated an ICC arbitration stemming from contracts with the Libyan state to construct a number of infrastructure projects in the Al Haya Valley (See, Cengiz İnşaat Sanayi ve Ticaret A.S. v. Libya, ICC Case No. 21537/ZF/AYZ). Following the outbreak of civil war in early 2011 in

Libya, Cengiz’s work camps were destroyed and the company was further prevented from working on the infrastructure contracts. Cengiz brought claims before the ICC under the Libya-Turkey BIT for breaches of FPS, fair and equitable treatment (“FET”), and for war losses. Cengiz sought in excess of $300 million USD.

Initially, Libya argued that Cengiz could not rely upon the Turkey-Libya BIT as it came into force after the civil war began in 2011. The tribunal disagreed, finding that many of the acts and omissions at issue occurred following the BIT’s entry into force. Following a hearing on the merits, the tribunal awarded over $50 million USD to the Claimant. In doing so, the tribunal rejected Libya’s argument that the claims should be assessed merely in light of a war losses clause in the BIT. The tribunal also rejected the Claimant’s attempt to recover future lost profits, limiting its compen- sation to the amount actually lost on the investment. A similar arbitration before a separate ICC tribunal concluded with a $21.9 million USD award for another Turkish investor seeking compensation for failures to protect construction investments in Libya during the civil war period (See, Etrak İnşaat Taahut ve Ticaret Anonim Sirketi v. State of Libya, ICC Case No. 22236/ZF/AYZ). However, not all claims against Libya were successful, take for example Tekfen and TML v. Libya (ICC Case No. 21137/MCP/ DDA). There, similar claims as in Cengiz and Etrak failed as the tribunal upheld jurisdiction but found against Claimant on the merits.

Likewise, not all claims brought by Turkish investors outside of Libya have been successful either, take as an example Muhammet Çap & Bankrupt Sehil Inşaat Endustri ve Ticaret Ltd. Sti. v. Turkmenistan (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/6). In that proceeding, a Turkish investor initiated an ICSID arbitration stemming from the cancellation of various construction contracts and the resulting non-payment. The Claimant invested in a local construc- tion company with more than thirty-two large-scale construction con- tracts. These projects included schools, parks, apartments, a convention center, and a shopping center. Several of these contracts were terminat- ed while others were not paid upon completion.

The Claimant brought claims under the Turkey-Turkmenistan BIT for expropriation, breach of FET and FPS – among others – and sought nearly $500 million USD in damages. Ultimately, the ICSID tribunal rejected the claims. In addition to finding that the Claimant failed to prove the State’s acts and omissions led to an indirect expropriation, the tribunal found that: (1) several of the claims should have been brought before local Turkmen courts as they were contract matters falling outside the BIT; (2) Claimant was unable to use the BIT’s most favored nation clause to im- port substantive protections from other treaties signed by Turkmenistan; and (3) the existence of customary international law rights did not create a separate cause of action. Without being able to invoke FPS and FET standards from other treaties or customary international law, Claimant had no claim for those violations.

The Muhammet Cap case serves as an important reminder to investors to consider two questions when considering initiating an investment arbitra- tion: (1) what are the substantive rights under the treaty; and (2) what are the procedural requirements under the treaty. It is crucial for investors to understand the specific substantive rights provided under the treaty in question. This includes a review of the treaty itself as well as decisions involving the treaty. Understanding whether one can import substantive rights from separate treaties can help determine exactly what claims can be brought. Without such an analysis, an investor runs the risk of making the same mistake as the Claimant in Muhammet Cap – claiming substantive violations for rights that the treaty does not actually provide.

Once an investor determines the specific rights at issue, they must ensure that any procedural steps required by the treaty prior to initiating arbitra- tion are followed, as well as ensuring that the claims brought are those allowed under the treaty. Procedural concerns potentially include jurisdictional issues –such as cooling off periods, admissibility issues, statute of limitations concerns, exhaustion requirements, or issues with the treaty’s definition of investor or investment. In Muhammet Cap, the tribunal noted that several of the claims brought by Claimant were required to be brought in local courts. Because the Claimant was required under the treaty to bring those claims locally, they fell outside the jurisdiction of the tribunal.

While Türkiye has more often been on the Claimant side in investor arbi- trations, a number of claims have been brought against the state as well. In 2011, Tulip Real Estate Investment and Development Netherlands B.V. initiated an ICSID arbitration regarding its investments in a Turkish real estate venture (See, Tulip Real Estate Investment and Development Netherlands B.V. v. Republic of Turkey, ICSID Case No. ARB/11/28). The Claimant invested in a local real estate company holding both mixed-use residential and commercial real estate assets. The Turkish State was the majority shareholder of the company. In 2010, the company terminated a contract for one of its more lucrative ventures. The Claimant brought claims under the Netherlands-Turkey BIT for indirect expropriation, FET, and FPS. Claimant sought a damages award of roughly $450 million USD. The tribunal rejected the claims, finding that the contract cancellation could not be attributed to the Turkish State, even though it owned a majority interest in the company. Though the tribunal did not fully analyze the issue, it also held that even if the acts were attributable to Türkiye, they would not have been a violation of the treaty.

Conclusion

In the future, we can expect that the number of investment arbitrations in Türkiye and the surrounding regions will continue to multiply as a result of increasing globalization. As such, it is crucial for investors to remain aware of their substantive rights and protections under the growing number of BITs relevant to investments in the regions. Given the nuance inherent in cross-border construction disputes, it is important to engage professionals experienced in such disputes in the region as they have the necessary expertise to evaluate the options available to investors. Knowledgeable counsel can ensure that the appropriate substantive violations are considered and that any pre-arbitration procedural requirements are completed. Doing so at the outset can help to avoid some of the pitfalls. Without that expert assistance, investors run the risk of limiting their own recovery or otherwise failing to recover for otherwise valid claims.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Diora Ziyaeva is a Partner at Dentons New York, focusing her practice on investor-state arbitration, international commercial arbitration, complex commercial litigation, and public international law. Dual qualified in Uzbekistan and New York, she brings 14 years of experience to successfully representing sovereign states and investors in over 30 significant international arbitration proceedings. Diora has earned recognition as a “Future Leader” in arbitration by Who’s Who Legal, and as one of the American Bar Association’s On the Rise – Top 40 Young Lawyers. Additionally, she is a Council on Foreign Relations Term Member, a certified mediator and arbitrator, and serves as an Adjunct Professor of Law at Cornell Law School and at Fordham University School of Law, specializing in teaching investor-state arbitration.

Dogan Eymirlioglu is a Partner at BASEAK Istanbul (a Dentons local partnership), leading the firm’s arbitration practice in Turkey. His professional focus encompasses domestic and international commercial arbitration, complex commercial litigation, and investor-state arbitration. Dogan serves as party counsel and arbitrator in ICC, UNCITRAL, ISTAC, and ad hoc arbitrations. He holds membership in the ICC Commission on Arbitration and ADR, as well as Istanbul Arbitration Center’s Companies Law and M&A Law Commission. Notably, he was the exclusive recipient of the 2019 Client Choice Awards for Arbitration & ADR in Turkey, as recognized by the Client Choice. Dogan is a member of the Istanbul Bar and previously held the position of deputy director at the French Chamber of Commerce in Turkey. Fluent in English, French, and Spanish, he brings a multilingual dimension to his practice.

Find more data-backed insights in our 2023 Construction Arbitration Report