This article was featured in Jus Mundi‘s 2023 Arbitration Statistics Report. The report offers a comprehensive comparative analysis of the 2023 annual statistics published by some of the world’s leading arbitral institutions, including the ICC, LCIA, SIAC, HKIAC, VIAC, DIAC, SCC, NAI, PCA, and ICSID. Covering caseloads, procedural innovations, diversity efforts, financial stakes, and state involvement, the report highlights key trends shaping international arbitration and calls for greater transparency and consistency across the sector.

THE AUTHOR:

José Emilio Ruiz Pineda, Foreign Legal Expert

Strides Towards Gender Diversity and Inclusion

Diversity is, without a doubt, one of the more complex issues in contemporary arbitration practice. Historically, the system has faced criticism for its lack of gender and geographical diversity. Arbitral institutions have taken up this issue, spearheading different initiatives and taking matters into their own hands. Initiatives include, for example, the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge, which was launched in 2016 and represents a commitment to promoting greater gender diversity in arbitration. Since then, many arbitral institutions have taken part in signing the pledge.

In 2022, ICCA published its updated 2022 Report of the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings, an initiative that includes representatives from most of the arbitral institutions included in this report. Notably, the ICC has championed a number of relevant initiatives, including its ICC Guide on Disability Inclusion in International Arbitration and ADR, which earned the ICC the ERA Pledge Award at the 2024 GAR awards.

Given this context, arbitral institutions and institutional courts consider gender parity when appointing arbitrators, which is reflected in their reports. This section highlights the percentage of women appointed by institutions, parties, and co-arbitrators where available.

Indeed, most annual reports disclosed the percentage of women sitting in arbitral tribunals, while others notably disclosed the percentage of women within their workforce. For instance, the SIAC revealed that women constitute 71 percent of their overall workforce, and the ICSID reported that 75 percent of the ICSID secretariat is composed of women across all levels – a welcome disclosure.

Turning to the percentage of women arbitrator appointments made by the arbitral institution, the parties and the co-arbitrators: In 2023, the ICC reported an increase in the appointment of women arbitrators, with 29.7 percent of the total confirmations and appointments, a minor increase from 28.6 percent in 2022. Of all women arbitrators confirmed or appointed, 47 percent were nominated by the parties, 37 percent by the ICC Court, and 16 percent by the co-arbitrators. For their part, the LCIA Court’s appointment of women arbitrators ‘reached near parity’ at 48 percent of all LCIA Court appointments. The remaining 39 percent of women arbitrator appointments were made by the co-arbitrators, and the final 21 percent by the parties.

At the SIAC, out of 164 arbitrators appointed by the institution, 60 were women, representing 37 percent of the total appointments. Similarly, at the HKIAC, out of 172 appointments made by the institution, 60 were women, accounting for 34.9 percent of the total appointments. Both the SIAC and the HKIAC did not report on the number of appointments made by the parties or co-arbitrators.

At the DIAC, similar to the LCIA, appointments made by its Arbitration Court reached near parity, with 47 percent arbitrators appointed being women. This is in stark contrast to the 22 percent of women appointed by the parties and the lower 15 percent of women appointed by the co-arbitrators.

At the VIAC, there was an increase in the appointment of male arbitrators, with only 34 percent of all confirmed arbitrators being women. Specifically, only 18 percent of party nominated arbitrators were women. However, 42 percent of chairperson nominations were women, as nominated by their co-arbitrators. In a stride to promote diversity a 52 percent of VIAC Board arbitrator appointments were women.

For its part, the SCC reported that 39 percent of the total arbitrators appointed by the institution, the parties, and co-arbitrators were women. The NAI notably observed that 54 percent of the total direct appointments made by the institution were women arbitrators, comparatively the largest share of institutionally led women arbitrator appointments. The ICDR, informed that out of 286 of its new arbitrations and mediator appointments, 49 percent identified as either female or diverse.

The PCA did not report figures regarding women arbitrator appointments in its annual report. Under ICSID, 22 percent of all reported arbitrator appointments made to ICSID cases were women. ICSID appointed 45 percent of the reported women arbitrator appointments, 18 percent were appointed by the respondents, and 5 percent by the claimants. Furthermore, 24 percent of women arbitrator appointments were made jointly by the parties, and the remaining 8 percent were made by the co-arbitrators.

In comparing the annual reports, it can be noted that most of the strides towards gender diversity are institutionally led rather than by the parties or co-arbitrators. Overall, the involvement of women arbitrators in international arbitration continues to grow, and the outlook appears promising.

Constitution of the Arbitral Tribunals

Generally speaking, an arbitration agreement or the parties in agreement will indicate the number of arbitrators that will resolve the dispute in the event of an arbitration. Less often, arbitration agreements are silent on this question. In such cases, parties fall back on the arbitration rules to provide guidance on the number of arbitrators that will hear a particular case. Often, the arbitral institution has to appoint the arbitrators for the parties.

In this respect, we examined what number of the arbitrator appointments were made by the institution and the type of arbitrator appointed. Where reported, we also looked at which type of tribunal is preferred – whether a three-member or a sole arbitrator tribunal – under the different institutional rules, based on the reported numbers and/or percentages.

The ICC Court made a total of 362 arbitrator appointments, 770 arbitrators were nominated by the parties, and 210 arbitrators (or chairpersons) were nominated by the co-arbitrators. Interestingly, under ICC arbitrations, parties agreed on the number of arbitrators in 86 percent of the cases. Of the constituted tribunals, 66 percent were three-member tribunals, while 34 percent were sole arbitrators, with the remaining 14 percent being fixed by the ICC Court. In cases where the parties did not agree on the number of arbitrators, the ICC Court submitted disputes to three-member tribunals in 20 percent of the cases, and to a sole arbitrator in 80 percent of the cases. In sum, the ICC reported that 60 percent of cases were submitted to a three-member tribunal and 40 percent were submitted to a sole arbitrator.

The LCIA made a total of 445 arbitrator appointments of 303 arbitrators. The LCIA reported that 48 percent of arbitrators were chosen by the parties, 36 percent by the LCIA Court, and 16 percent by the co-arbitrators. All in all, 56 percent of constituted tribunals were three-member tribunals, while 44 percent were sole arbitrators.

The SIAC, for its part, only reported that it made a total of 164 arbitrator appointments. Of these, 126 were sole arbitrators, and 38 corresponded to three-member tribunals. Specifically, 147 appointments were made under the SIAC Arbitration Rules 2016, 3 appointments were made under other rules, and the remaining 14 were made in ad hoc arbitrations. Likewise, the HKIAC only reported that it made a total of 172 arbitrator appointments, 111 of these were sole arbitrators, 30 were co-arbitrators, 28 were presiding arbitrators, and 3 were emergency arbitrators. The DIAC reported that 64 percent of tribunals were presided by a sole arbitrator and 36 percent consisted of a three-member tribunal. Out of the 143 arbitrators appointed, 40 percent were selected by the Arbitration Court, 42 percent by the parties, and 18 percent by the co-arbitrators.

The VIAC did not report on the number or type of arbitrator appointments. The SCC revealed that out 250 total appointments, 92 arbitrators were appointed by the SCC, 148 arbitrators were appointed by the parties, and 10 arbitrators were appointed by the co-arbitrators. The NAI only reported that out of a total of 84 arbitrator appointments, 53 appointments were made by the parties and/or co-arbitrators, and 18 appointments were made pursuant to the NAI’s list procedure, and 13 appointments were appointed by the institution. The ICDR, for its part, did not report on the number or type of arbitrator appointments.

The PCA, within its services, acts as appointing authority (and as designating authority, though the PCA did not report on this) under certain circumstances. In 2023, out of 58 requests received under this mechanism, the PCA appointed 12 arbitrators, with 4 requests pending. The PCA did not report on the number or type of arbitrator appointments. Under ICSID arbitrations, 77 percent of arbitrator appointments were made either by the parties or by the party-appointed arbitrators, with the remaining 23 percent being appointed by ICSID, based on the agreement of the parties or applicable default provisions. It is important to note that due to the nature of the disputes that the PCA and ICSID administer, tribunals are often composed by a three-member tribunal.

Challenges to the Appointment of Arbitrators

In international arbitration practice, arbitrator appointments may be challenged in the process, either due to genuine concerns or as part of the challenging parties’ strategy. This occurs notwithstanding the fact that arbitrators are increasingly making disclosures to avoid giving rise to doubts about their independence and impartiality.

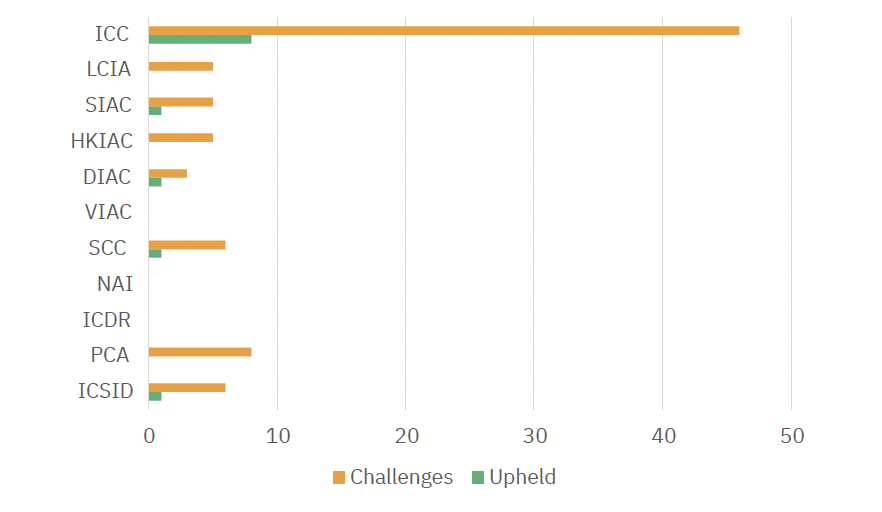

In this context, arbitral institutions reported on the number of challenges their confirmed arbitrators received. Initially, the intention was to compare these numbers against the numbers from 2022; however, the data was not readily available for some of the covered arbitral institutions. Therefore, the following graph shows the number of challenges received by each institution in 2023 and what number of them was ultimately upheld.

In 2023, the ICC reported a total of 46 challenges, of which 8 were upheld. Under LCIA arbitrations, the reported number of challenges was low with only 5 challenges, two of which were rejected, in one instance the arbitration presented its resignation and in two cases the applications remain pending. The LCIA credits this to its robust appointment system, where disclosures are dealt with ‘efficiently and transparently.’ Additionally, a welcome initiative by the LCIA is its ‘Challenge Decision Database’. The database includes decisions from 2010 to 2022.

Under SIAC arbitrations, 5 challenges were received against arbitrators in 2023, which were decided by the SIAC Court of Arbitration, with 1 being upheld and 4 being rejected. Under HKIAC arbitrations, 5 challenges were submitted, 3 were pending at the end of 2023, 1 resulted in the resignation by the challenged arbitrator, and 1 was withdrawn by the challenging party.

Under DIAC arbitrations, 3 challenges were received against arbitrators. In the first case, the arbitrator resigned before the challenge was resolved. In the other two cases, which were resolved at the beginning of 2024, 1 challenge was upheld, and the other one was denied. Under SCC arbitrations, six challenges were made, 5 challenges were dismissed, and 1 was upheld. The VIAC, NAI and ICDR did not report on the number of challenges received.

The PCA resolved 8 challenge requests in relation to 11 arbitrators, with 1 challenge pending, and 4 requests withdrawn or rendered unnecessary, the PCA did not specify if the challenges were upheld or denied. For its part, the ICSID revealed that under their proceedings, six challenges were recorded, the lowest in the past decade, 5 of which were denied and 1 being upheld.

In summary, the annual reports indicate that the existing disclosure and pre-appointment processes used by various arbitral institutions effectively achieve their intended goals. New developments, such as the SCC disclosure policy mentioned above, will further strengthen the disclosure processes, with an aim at reducing conflicts of interest. Moreover, the reports reveal that the standard for challenging an arbitrator remains high across the selected arbitral institutions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

José Emilio Ruiz Pineda is a Honduran-qualified lawyer that specializes in international commercial (and investment) arbitration. He frequently advises and has participated in arbitrations under various arbitration rules (including the ICC Rules, SIAC Rules, the UNCITRAL Rules). Emilio holds an LL.M. in International Arbitration and Business Law from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Discover more insights into the global trends shaping institutional arbitration in 2023 by exploring the full Arbitration Statistics Report now.

* The views and opinions expressed by authors are theirs and do not necessarily reflect those of their organizations, employers, or Daily Jus, Jus Mundi, or Jus Connect.

* The arbitral institutions have been selected from the perspective of the author, a native Spanish and English-speaking Amsterdam-based international arbitration practitioner.