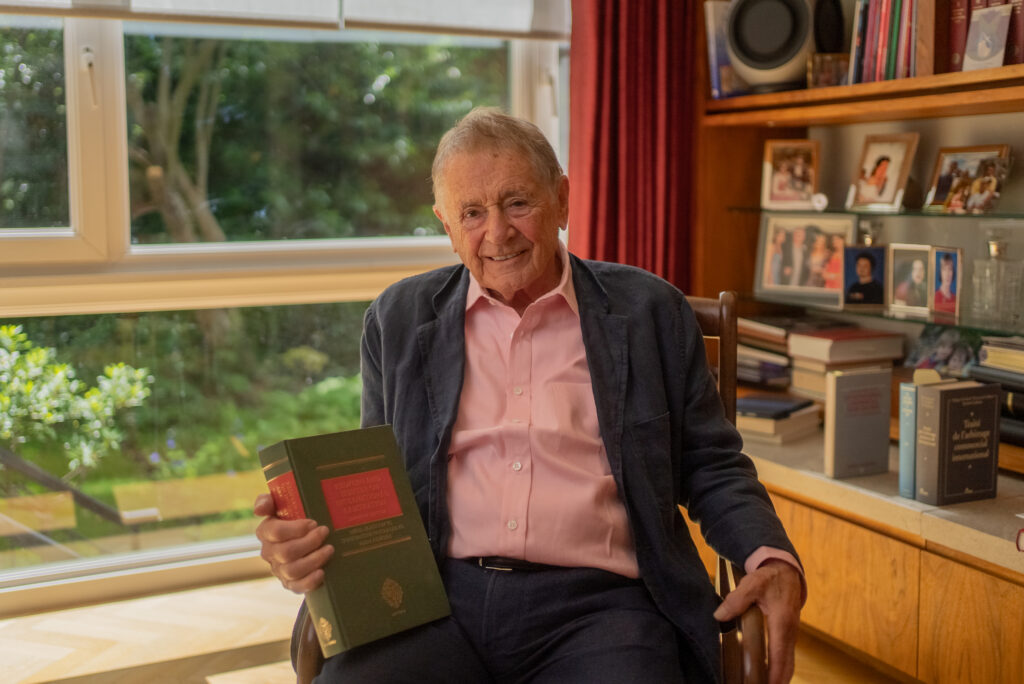

Few names resonate as powerfully as Alan Redfern in international arbitration. As a leading authority in the field, Redfern’s contributions have shaped modern arbitration practices and principles.

Redfern is best known for the famous “Redfern Schedule” and his seminal work, Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration, co-authored with his colleague and friend, Martin Hunter and available on Jus Mundi. This cornerstone treatise has guided countless practitioners and students through the complexities of arbitration, establishing itself as a definitive resource.

Now in its Seventh Edition, Redfern reminisces on the book’s inception, the enduring legacy of his work with Martin Hunter, Constantine Partasides, and Nigel Blackaby, and the developments in international arbitration and tech he has witnessed during his illustrious career.

This interview also honors the memory of Martin Hunter, who left a profound impact on international arbitration, including through his visionary ideas and commitment to education. Hunter’s collaboration with Redfern produced a work that remains indispensable for both seasoned practitioners and students.

Explore the Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration and more from the Oxford University Press Law Library on Jus Mundi

How did the very first edition of the Redfern & Hunter on International Commercial Arbitration come to be? What inspired you and Martin Hunter to write this comprehensive book?

I have to go back a little bit into history for that, because Martin and I go back a long time.

Mid 1960s, I became a partner in Freshfield, where I had trained as a lawyer after getting a law degree at Cambridge. I was told that I was going to be a litigation partner. I think I was probably the first litigation partner in one of the big city firms.

The Senior Partner, Charles Wishaw, who was a very experienced lawyer in oil, advised the Kuwait government on their concessions. He called me one day and said: “Alan, I’ve been invited to advise the government of Kuwait in a dispute with an Italian company, and I would like you to help”. So, I went to Kuwait and met the Crown Prince, Sheikh Jaber. He explained that an Italian engineer had come over to Kuwait and said [they could] build a petrochemical project for the country. He took a deposit of 7 or 8 million Pounds and the Sheikh signed an agreement. Then the government had Danish consultants look at it and they said it’s just not viable.

So, the government decided not to proceed with the [project] and said they’d like their money or some of it back. The Italian company said: “Well, you’re breaking the contract”, and started an arbitration. That was my first international arbitration. With the Italian lawyer, I had to sort of put in place all the building blocks for an arbitration. We had a tribunal, we had a claim, but how is it going to be dealt with? That was a very good learning experience for me.

Then, at about the same time, one of the corporate partners said: “Alan, I’ve got a case for a construction company against the government of the Republic of Sudan, and that [is] going to arbitration in the Hague at the Peace Palace. I would like your help on that”.

So, there I was, mid sixties, with a basic litigation department, asked to help run arbitration. I said to [a corporate] Senior Partner I need[ed] another qualified lawyer to join me. He said: “We’ve got this young man called Martin Hunter. He’s just been assigned to our corporate department. I’ll see if you can borrow him for these two cases”. As Linda [Martin Hunter’s wife] said to me recently: that was a loan that was never repaid because Martin stayed with me and the department until he left to become a professor and start his second highly successful career .

So that was the background.

It must have been 1980s. Martin was approached by Sweet & Maxwell, the law publishers, and they said “People are starting to talk about international arbitration and there’s no English book on it. Would you be interested in writing it?”. Martin said, “I’ll do it if Alan will do it with me”. I said: “You’ve got to be joking. We’ve got a lot of work! We’re bringing in new partners, new assistants. We’re traveling a lot, both of us”. I was doing a lot of, at that stage, construction arbitrations for the government of Kuwait and he was working for the Kuwait National Petroleum Corporation. Sometimes, the only time we met was when we were both in Kuwait.

He said: “Look, we can do it in our spare time. We can do it on weekends, holidays, and so on. And if we don’t do it, somebody else will”. So I said: “Okay, Martin, let’s do it”. And he was terrific. He said, “We’re going to have eight chapters: we’re going to go from the commencement of an arbitration to the award, to the enforcement of an award. That’s going to be the structure of the book, and we’ll write four chapters each. You can be editor of all the scripts, and I will deal with the business”. He would deal with the publishers; with translations (that came a long way), and he would deal with marketing and all that kind of exercise, because he knew I just liked writing and being a lawyer.

That’s how it started.

So, it was really a call from Sweet & Maxwell that got us going.

How has the book evolved over its various editions? What changes or updates do you consider the most significant?

It’s changed a lot. The First Edition, which I imagine is my favorite, was almost a pocket edition. It was a distillation of what Martin [Hunter] and I had learned actually doing arbitrations. I’d read the Swiss and the French; he’d read a lot of American stuff. But it was a distillation of what we knew; very few footnotes, very practical. I think people loved it, especially practicing lawyers, because you could get straight to the point without a lot of theoretical discussions.

Then, of course, it got more complicated. I suppose we ourselves learned a little bit more about arbitration, but also we were obviously trying to talk about international arbitration. I suppose the first book was mostly European-orientated, and now the aim was to make it more international. We could only do that because we were Partners in a law firm which had offices all around the globe. But it became clear that it was going to be too much for the two of us, and so we would need to bring in two people to help us. That was the first significant change.

We had two good lawyers: Constantine Partasides and Nigel Blackaby. Constantine has since gone off and founded his own very successful law firm specializing in international arbitration. And, of course, he had lots of contacts, which were very useful to us. Nigel went to the Washington branch of Freshfields and developed a very big practice in Latin America. Crucially, he wrote what, in my view, is a really superb chapter on investment arbitration, which was coming along at that time. That was one significant change in the book: we added a chapter on investment arbitration. It was no longer called Redfern and Hunter on International Commercial Arbitration. It was now simply Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration. I have often said to people, if they want a very quick, good guide to investment arbitration, just read Chapter 8 of Redfern & Hunter, because that has got it nailed.

As subsequent volumes evolved, they simply got more complex because we had more information coming in from more countries. The problem is to filter it down because we want to try and keep it as a one-volume book. We want the Student Edition, which is very important to us now, to be something that students can carry in their backpack. So that is quite a struggle, because there’s so much information coming in. You could write a whole chapter on China. And then, we have to put that down to a few paragraphs, which is a pity, but it’s the way it’s evolving.

You talked about the Student Edition of Redfern & Hunter. How have you contributed to this educational aspect of the book which was very important to Martin Hunter, who wanted it to be accessible for students all around the world?

It was his idea: he said we ought to have a Student Edition He persuaded the publishers that would be a good idea: a paperback without any appendices (which cuts down a lot). He said, quite rightly, that nowadays, people didn’t need a book with the ICC Rules of Arbitration or the UNCITRAL Rules because you could get that on your laptop quite readily, and that’s what students would do. So, we were able to cut down the appendices.

I suppose nowadays you just put it on your screen anyway. But, you know, there was a time when it was very useful to have all that for practitioners, but not for students.

And so, we produced the Student Edition, which I think outsold the hardback, actually. Martin had a great passion for teaching. His father had been a teacher at a very prestigious English school, Winchester, and I think Martin just had that in his blood.

You mentioned legal information has now become much more readily accessible. How do you view this digital revolution and the impact of platforms like Jus Mundi for practitioners?

It’s an incredible development; it’s a fantastic thing that happened! For first editions of Redfern and Hunter, I remember going to the law library to chase up references. I went to the British Institute of International and Comparative Law in Russell Square because they had a very good library. If I wanted an English case, then I had to go to the law libraries in the Temple. If I wanted an international case, I had to go to the British Institute or just ask friends from France: “Could you please send me a copy of the judgment of the Cour d’Appel in such and such a case?”. And now it’s all online. It’s incredible!

Do you have any memorable moments or anecdotes of your time with Martin Hunter, Constantine Partasides and Nigel Blackaby?

We took Nigel and Constantine to a hotel in the country. Martin had said it would be a good idea to get away from London so that we’re not interrupted. We sat down in this hotel room and they started mowing the lawn outside so that we couldn’t talk to each other, which was slightly frustrating, but didn’t stop Constantine and Nigel agreeing to join us first of all as assistants, and then as editors, with Martin and myself as contributing editors. So that was quite an interesting moment. When Constantine and Nigel boarded the ship.

I think the best moment, perhaps, with Martin and myself, was not having dinner together on Valentine’s Day in a hotel in Kuwait, which was not quite what Valentine’s Day was designed for.

When we finished the book, at the same time, I had bought some land in Savoy, in the town where my wife lived and went to school. It was on the edge of the forest. We started building a house there.

1985, I think it was. The house was pretty finished in the sense that there was a structure, but there was no paint on the walls, and the furniture was mostly in boxes, although we did have a nice fireplace. And Martin and Linda [Martin Hunter’s wife] came over. They drove over from England to join us. And Linda, who’s a very good photographer, compiled an album, which she called “Finishing the book”. I think that was a very good memory.

Looking into the future, what do you hope your legacy in the field of international arbitration will be?

I think the book. I mean, there’s the Redfern schedule, which I devised in 2000, and that, again, was a very practical, pragmatic kind of thing. I was on a tribunal with Lord Griffiths, who’d just left the House of Lords and was starting to set himself up as an arbitrator and a mediator. We went through the usual requests for documents phase: “We want to see these documents. We don’t have them, or you can’t see them because they’re legally privileged, or you can see some of them but not all of them”. This was evolving over the years: starts off as a big request for documents, gets filtered down, and then finally they can’t agree anymore. So, they come to the arbitrators and say, “Make a decision. Order or don’t order production of these documents”. Hugh Griffiths said: “How on earth are we going to deal with this?” I suggest[ed] we don’t deal with it: we let the parties deal with it, because they’ve been talking to each other for the last three months; they’ve been writing to each other; they’ve been meeting. They know what their final position is, so just ask them to set down their final position.

Four columns:

- Schedule one: these are the documents we want;

- Next column: this is why we want them;

- Answer: you can’t have them for this reason (professional privilege, whatever it is) or you can have them;

- Fourth column: decision of the tribunal.

Lord Griffith said: “Oh, brilliant!” And then with a wry smile, he said: “We’ll call it the Redfern schedule”. That was supposed to be just for that arbitration. Then, Johnny Veeder heard about it. And suddenly, people were saying: “We’ll have a Redfern schedule”. I think the high spot for me arrived when Jan Paulsson and I were talking at a conference in Brussels. He said: “I just got back from Vietnam, and they’ve published a book on international arbitration. Look what it says”. Neither of us could read Vietnamese, but there was “Redfern schedule”. And it’s gone on.

I met a young counsel, and he said: “Alan, I spent the last three days and nights working on a Redfern schedule, and I have lost the will to live”. And I can understand it, but it’s going to be a lot easier, isn’t it? Because now it’ll be done by artificial intelligence. There’s certainly going to be a lot less demand on people. It’s going to be quite a revolution, I think.

What do you think the impact of artificial intelligence tools such as Jus Mundi’s will be on international arbitration?

It will cut down the legwork. It will cut down all the hours that people have to spend looking for documents and evidence. Properly run, it could focus the case more on what’s really involved. Properly developed, it could help the lawyers put forward arguments that are tenable and not some sort of wild arguments.

What advice would you give to aspiring arbitrators or authors like you’ve been?

I’d start with young lawyers and I’d say: don’t go into the law because you think you’re going to make a lot of money. Go into the law because you have a feeling that that is what you want to do, because you believe in principles of law, you believe in a society of law, you believe in justice, and that’s why you become a lawyer, not to get rich. I think if that is your approach, you’re going to be a good lawyer, whatever branch you go into.

I would always go into the area that I went into because I think that’s just more fun and more challenging. And if you get into that area, then certainly you ought to think about arbitration because that gives you a chance as a young lawyer to get on your feet and argue a case, which is probably what you really want to do. You don’t want to be sitting behind somebody else. And I think with that kind of enthusiasm, you can get there.

If you want to be an arbitrator, then that’s quite difficult because people, naturally, and especially if there’s a lot of money involved, want to go to established arbitrators. So you’ve got to be prepared to start perhaps as a tribunal assistant, sitting with a tribunal and taking part in the deliberations or listening to the deliberations and generally making your name like that. Or writing about it.

But I think doing it is probably better than writing about it. Learning by doing. That’s what we do. That’s really what we do.

Note: This interview is a transcription of a video interview with Alan Redfern shot on July 12, 2024, edited for clarity and readability. The full interview is available here:

Enhance Your Legal Research with the Oxford University Press Law Library

Inspired by Alan Redfern’s reflections on international arbitration? Combine the expertise of Oxford University Press with Jus Mundi’s AI-powered search technology to conduct faster, more accurate research.

Access a rich collection of international law and arbitration resources, featuring insights from renowned practitioners. Discover a unique combination of books and journals on key topics in Investment Arbitration, International Trade Law, and Public International Law.