THE AUTHOR:

Ryan Stephan, Legal Content Marketing Intern at Jus Mundi & Paris II Assas Master 2 Graduate

The Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system was originally designed to serve as a shield to protect foreign investments, primarily from wealthy economies, essential to fostering economic growth in developing countries. However, there is growing concern that the system now acts as a sword for investors from developed nations, harming the economies of developing countries and penalizing useful reform measures with substantial financial awards.

In response to these concerns, researchers have sought to answer the critical question: is ISDS beneficial for developing economies? Legal scholar Susan Franck has examined criticisms of investment arbitration through empirical studies of known disputes (Franck 2007, 2009), providing valuable data and stimulating constructive debate. Her research is now often cited to support the notion that the system does not unfairly subject developing countries to arbitration and that they do not disproportionately lose their cases. However, Franck acknowledges that her work has limitations due to the relatively small dataset, which comprises 102 awards from 82 cases and only 52 final awards resolving treaty claims.

Since 2009, the use of ISDS has increased significantly, with up to 69 new cases in 2013 alone. As of June 10, 2024, more than 946 concluded cases are available on Jus Mundi. Given this new wealth of data, it is time to re-examine the question and see what the numbers reveal.

Is ISDS the shield that protects investors or the sword that harms developing economies?

To find out, we will first analyze data gathered from Jus Mundi’s database. Next, we will assess whether the balance between investor rights and State regulatory powers is maintained. Finally, we will determine if Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) effectively attract foreign investments.

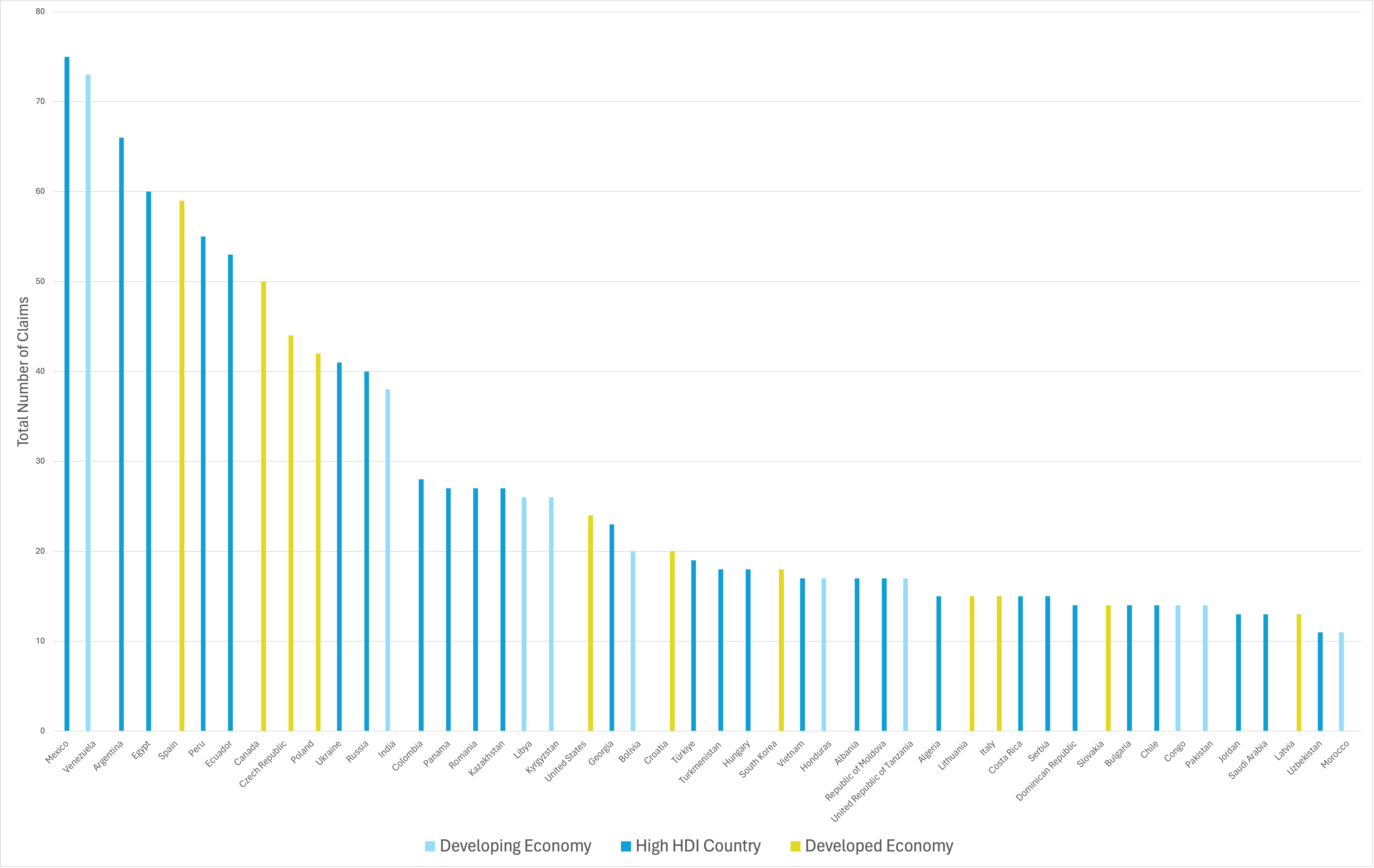

Developing Countries are Subject to More Claims

For the purpose of this study, I examined the 1,778 investment arbitration claims available as of June 10, 2024, on Jus Mundi’s international arbitration database. The dataset includes claims filed under the rules of various arbitration institutions, including the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), as well as ad hoc arbitrations conducted primarily under the United Nations Commission for International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) rules.

The countries were classified into three groups using a mix of the World Economic Situation and Prospects 2023 Country classification and the UN Development Programme Human Development Index (HDI). The three groups are:

- developed economies (e.g., Switzerland, France, and Australia),

- High HDI countries (e.g., Brazil, China, and Ecuador), and

- developing economies (e.g., Lebanon, India, and Morocco).

The table with the results can be accessed here.

What interesting trends can be noted?

First, the data shows that Developing and High HDI countries are disproportionately targeted with arbitration claims, compared to the amount of global foreign direct investment (FDI) they receive. Although they receive a fraction of the global FDI, they face a much higher percentage of claims. For instance, in 2022, Latin American countries received 9.3% of global FDI but are subject to 27.5% of all ISDS claims. Similarly, in the same year, African countries only received 5.4% of global FDI inflows but are subject to 16,2% of all claims. In general, developing and High HDI countries face 78.6% of all arbitration claims.

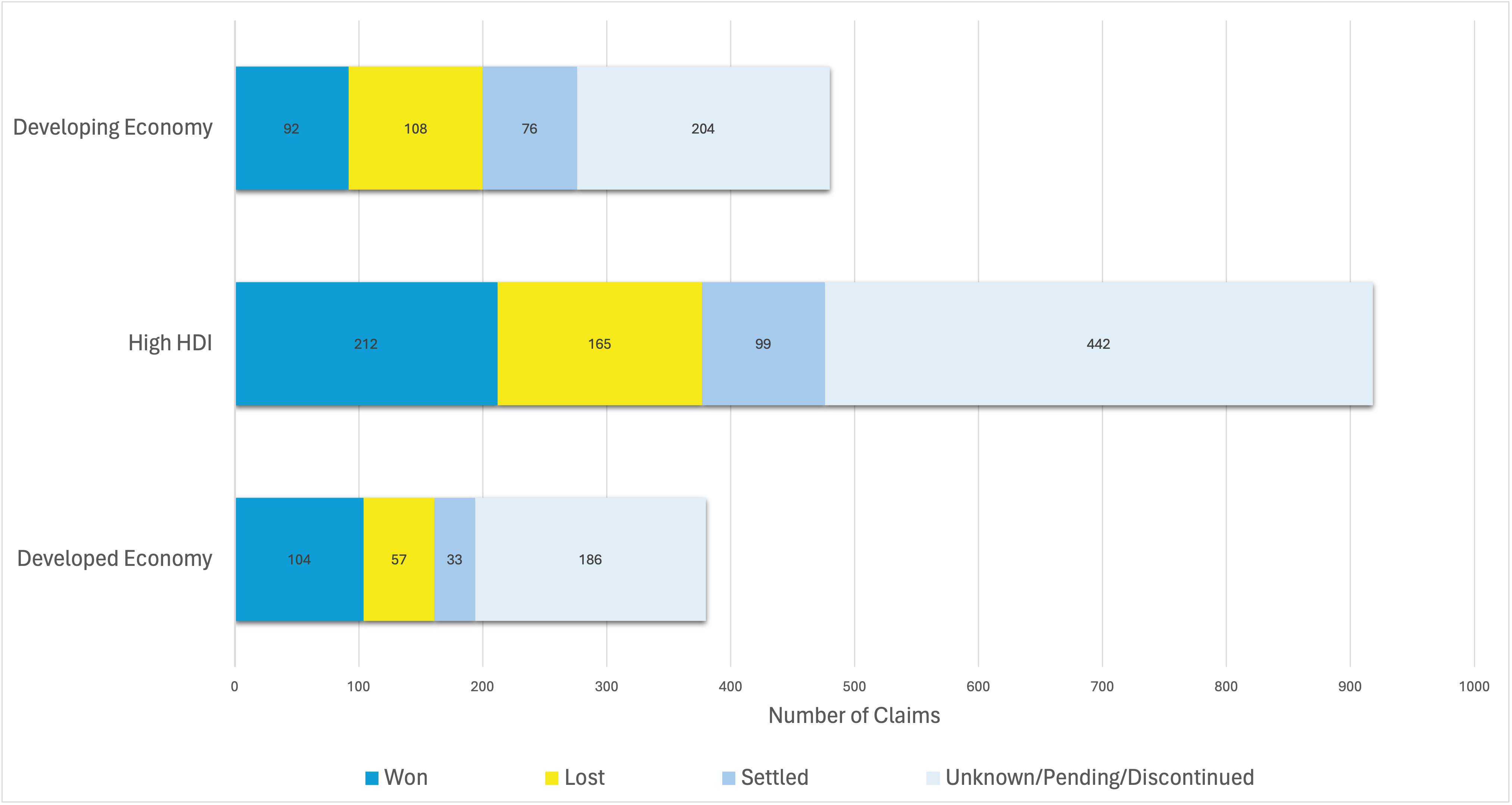

Reflecting on Susan Franck’s work, her research suggested that developing countries are not disproportionately targeted by claims under the system and that investors do not win the majority of cases. She adds that “governments (57.7%) were more likely than investors (38.5%) to win cases and have no damages awarded for alleged treaty breaches.”

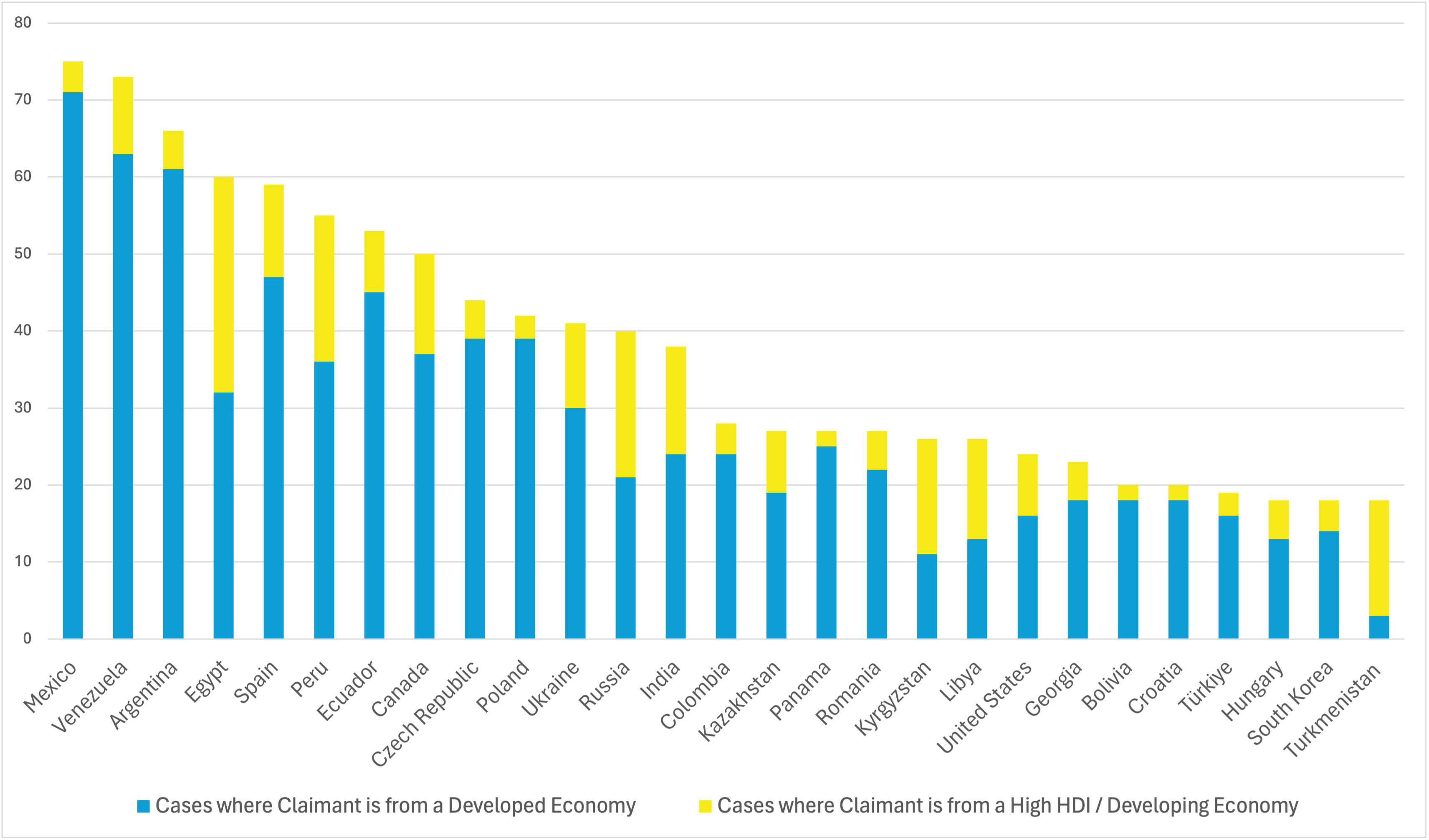

However, the more recent and extensive data seems to disagree. On average, 72.8% of the claims filed against all categories of countries come from investors of developed countries. This is despite the fact that only 21.3% of respondent States are in the “developed economies” category.

Developed countries also tend to win more cases, with an average success rate of 53,6%. Compared to the success rate of 44,5% for High HDI countries and 33,3% for developing countries, we can conclude that investors are much more likely to win a case against a developing economy than against a developed one.

These results could be explained by a number of factors and do not necessarily point to an unfairness of the system. However, they do shed some light on certain realities:

- The ISDS system poses disproportionate challenges to both developing and High HDI countries relative to the amount of FDI they receive.

- Developing economies bear a significant burden of losses within the system, indicating a potential lack of preparedness or capacity to mitigate the consequences of arbitration rulings.

- The current ISDS system exhibits a bias in favor of investors from developed economies compared to developing and high HDI nations.

One interesting factor brought forward is that many governments, – the majority of developing economies -, are often unaware of investment treaty law and its implications. As a result, when implementing new measures that could affect investments, they do not follow rigorous legal procedures that could mitigate the chances of successful claims against them. This is different from High HDI countries which tend to give a great deal of thought to their new policies to protect them against potential arbitration claims. These procedures include, among others, informing investors of policy changes and allowing them sufficient time to prepare for new regulations. In contrast, developing countries may also lack the expertise to provide official justifications for their policies. For instance, in Lebanon, sources in the government confirmed to us that no consideration is given to whether new policies might affect investors and potentially expose the country to arbitration risks.

These findings prompt us to consider the delicate balance between investor rights and State regulatory powers.

The Balance Between Investor Rights and States Regulatory Powers

In recent decades, the use of investment arbitration expanded beyond its role of protecting investors against blatant State wrong-doings, such as outright takings of property and denial of justice. Investors are now able to form claims against a broader range of issues for governmental actions displaying “a relatively lower degree of inappropriateness.”

This expansion can be seen with the increasing number of claims of indirect expropriation, where almost any legislative, regulatory, or administrative action by the State amounts to a “measure” to which investment protection standards may apply. In the majority of cases, an indirect expropriation is based on the effects of the measures on the economic value or substantial property interests of the investor (the sole-effect doctrine). In other words, there is greater emphasis on how such measures affect investors financially rather than their underlying purpose to serve the public interest. This directly hinders the sovereignty of signatory States when changing policies in the general interest of their people and country.

There are numerous examples of cases where host States were sued for enacting legitimate measures that indirectly affected the value of an investment. For instance, in Bear Creek v. Peru (2017), the dispute arose from the contentious Peruvian Santa Ana Mining Project, which faced significant opposition from local communities due to environmental concerns. Intense protests led to the Peruvian government’s revocation of the decree allowing the project. Despite Bear Creek’s lack of necessary permits and widespread local opposition, the tribunal ruled that Peru had indirectly expropriated the investment, awarding Bear Creek over $18 million in damages and 75% of arbitration costs.

South Africa’s Black Economic Empowerment Policies are another pertinent example. These policies were designed to address the economic inequalities stemming from apartheid by promoting the inclusion of historically marginalized groups (African, Coloured, and Indian population groups) in the economy. These policies faced a challenge in the case Foresti v. South Africa (2010), which raised significant public concern and ultimately prompted the country to withdraw from the ISDS system.

However, it is also important to note that this criticism is being heard by an increasing number of tribunals who are giving due weight to important concepts such as the right of States to regulate, the margin of appreciation, and the principle of proportionality.

As a result, many countries have taken action and have started changing their approach to ISDS. To date, the ICSID Convention (1965) has been terminated by Bolivia (2007), Ecuador (2009) and Venezuela (2012). All three had multiple high financial stakes and treaty-based investor claims were filed against them. Numerous countries have also terminated their BITs, either unilaterally or jointly. Notable examples include Bolivia, Ecuador, and Indonesia. South Africa has also removed itself from the ISDS system. Meanwhile, countries like South Africa, Brazil, Australia, and India have adopted alternative strategies, either by resorting to State-State dispute mechanisms or by significantly modifying their BITs.

The Limitations of the Good Governance Narrative

Proponents of the good governance narrative argue that imposing financial penalties on host States for breaching governance standards can discourage the mistreatment of foreign investors and incentivize reforms in legal and bureaucratic practices. However, studies indicate a different reality.

A recent case study of five developing countries (namely Kazakhstan, Nigeria, Turkey, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan) reveals that many government officials are unaware of investment treaty law, its implications, and ongoing procedures arising out of it. Even after becoming aware of it, when officials get involved in those procedures, they often do not reform the disputed measures or other measures related to foreign investment.

Moreover, public awareness of these cases remains limited despite their significant consequences on public affairs. For example, in Ampal-American and others v. Egypt (2017), and Unión Fenosa Gas v. Egypt (2018) Israeli and Spanish investors were awarded a total of $2.7 billion, which is 1.6 times the amount Egypt spends annually on energy. Despite this, the Egyptian media scarcely covered these cases, despite their enormous impact on the public treasury.

As a result, ISDS mechanisms do not effectively incentivize host States to enhance their legal practices; rather, they primarily serve to provide a more favorable resolution method for foreign investors, sometimes at the expense of national businesses. In fact, another study indicates that the availability of ISDS at the international level reduces incentives for host States to improve domestic governance mechanisms and practices. Because foreign investors rely almost exclusively on arbitration, national courts are not encouraged to apply international practices or incorporate international legal standards. Consequently, foreign investors receive more favorable treatment through access to top-tier international courts, compared to local commercial parties, who must navigate courts with limited experience in international trade.

ISDS, a Magnet for Foreign Investments

The final main argument to support ISDS is that it allegedly attracts foreign investors by providing a sense of security and stability, which encourages vital investment in countries that might otherwise be overlooked.

Recent literature on investment treaties and investment flows presents mixed findings. Some studies suggest a positive association between BITs and foreign investments, but others find no significant impact. Interestingly, a majority of studies suggest that countries facing higher political risk tend to attract more FDI through BITs. Research on developed countries generally supports BITs as beneficial for FDI inflows, as evidenced by the positive impact of BITs on outward FDI from OECD home countries (Egger, P., & Pfaffermayr, M. (2004); The impact of bilateral investment treaties on foreign direct investment; Journal of Comparative Economics, 32(4), 788–804).

India provides a good example, as one recent study confirms the positive role of BITs in attracting FDI in India, providing protection and commitments to foreign investors. The research also suggests a direct relationship between the number of BITs and the volume of FDI, especially when these treaties are established with potential investor countries and are supported by factors such as economic size and liberal FDI policies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ISDS system is an investor’s armor that clearly creates a predictable and investor-friendly environment essential for attracting FDI, which is crucial for the growing economies of developing countries. Therefore, protecting investors’ rights is crucial.

The issue is that these rights are increasingly weaponized to outweigh the signatory States’ ability to regulate for the public good. This imbalance is particularly problematic for developing States, which are disproportionately targeted compared to the benefits they receive from the system, prompting some to abandon investor-State arbitration altogether.

For this reason, it is important to continue conversations about reforming the system to maintain its advantages while addressing its shortcomings. The goal is for BITs to strike a balance between State regulatory powers and investors’ rights, allowing for safe investment without compromising a country’s sovereignty. Ultimately, the aim is to protect investments while encouraging new regulations in developing countries to foster development and create a more secure, investor-friendly environment for both national and foreign investors, perhaps eventually rendering ISDS unnecessary.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ryan Stephan is a Legal Content Marketing Intern at Jus Mundi where he worked on legal publications and editorial projects. He holds a Master 2 in International Economics Law from Paris II Panthéon-Assas where he specialized in International Investment Arbitration, International Commercial Arbitration and International Trade Law. Ryan previously completed several internships with international organizations, multinational companies, and arbitration firms, including Derains & Gharavi and the World Trade Organization in Geneva. He will soon take the French Bar Exam.