Concepts and Foundations

THE AUTHOR:

Naimeh Masumy, Research Fellow at Deakin University & PhD Candidate at Maastricht University, Deakin University

Explore our comprehensive series examining the challenges of applying statutory rates, commercial benchmarks, and compound interest in international disputes. Through case law and evolving practices, it examines how statutory rates often misalign with market realities, the uncertainty of commercial floating rates post-LIBOR, and the contentious application of compound interest with unclear doctrinal foundations.

This comprehensive three-part series delves into the legal foundation governing interest under public international law, focusing on the determination of interest rates, applicable periods, and calculation methods. It underscores challenges presented by conflict of laws analysis, the opacity of the CISG framework in providing a robust normative basis for interest rates, and the divergent approaches to characterizing compound interest across domestic laws and arbitral rules.

The series highlights critical issues, including the lack of accurate financial benchmarks—exacerbated by the phase-out of LIBOR— and the failure to account for industry-specific risks, inflation variations, and market realities. To address these gaps, it proposes a nuanced framework for arbitrators to award interest that better reflects these factors, offering a more equitable and realistic approach to interest determination.

Definition of Interest

Interest is a well-known component within the archetype of investment arbitration compensation, as well as a well-established remedy for the loss of the use of money. The concept of interest is largely predicated on the economic reality that asserts a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow due to its potential earning capacity, as explained in the theory of Interest. Interest is a fundamental concept in finance, reflecting both the time value of money and the opportunity cost of capital. Conversely, money received in the future has a reduced value in the present due to the opportunity costs. The importance of interest is further emphasized by the principle of compound interest—described by Albert Einstein as “the eighth wonder of the world”—which illustrates how interest accrues over time, leading to exponential growth (Tony Robbins, Money: Master the Game, Simon & Schuster 2014).

The Legal Basis Governing Interest Rate in Investment Arbitration

- In treaty or commercial disputes resolved through arbitration, serves as compensation for delays in settling monetary claims, addressing the “loss of investment opportunity” or the “loss of the use of money” that the claimant could have otherwise utilized (Borzu Sabahi, Compensation and Restitution in Investor-State Arbitration (Kluwer Law International 1998) pp. 85–93, ch. 6, sec. 6.4 ‘Supplemental Damages in Private Investment Law: Interest’).

- Paying interest in anchored in the principle of “full reparation,” which aims to restore the claimant to the position they would have been in had the wrongful act not occurred (John Y Gotanda, ‘Awarding Interest in International Arbitration’ (1996) 90 American Journal of International Law 40, pp. 40–63).

- In calculating economic damages, courts consider the time value of money, applying interest to future losses to discount them to present value or to past losses to account for the time the claimant was deprived of their money (ILC Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts with Commentaries).

- The International Law Commission (ILC) advocates for the inclusion of interest when assessing state responsibility, and arbitral tribunals frequently incorporate interest in their final awards to ensure full compensation (Geraldo Vidigal and Stephanie Forrest, ARSIWA Part Two, Chapters I and II: Remedies (Oxford University Press 2022). In Iran v. United States, 16 Iran-U.S. C.T.R. 296 (1987), the tribunal clarified that interest is part of overall compensation, not a separate cause of action. Similarly, in Vivendi v. Argentina II, Award, 9 April 2015 it was affirmed that awarding interest to an injured claimant is a common practice in international arbitration.

- Overall, the inclusion of interest is a vital element in ensuring full reparation in arbitration cases.

The Hazy Foundation of Interest Rate within the Context of Investment Arbitration

The principles underlying interest rates in arbitral tribunals are not always clear-cut. When arbitrators address the rate of interest, they usually look to the parties’ agreement for any provisions explicitly addressing these issues (Bechtel, Inc. v. Iran, 14 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 149, 162 (1987); Final Award No. 6230 (ICC 1990), reprinted in 17 Y.B. COM. ARB. 164, 175-77 (1992)). However, if the agreement is silent or ambiguous regarding interest, the arbitrator usually performs a ‘choice-of-law’ analysis to select the law of a particular country and apply it to resolve the interest claim (Final Award No. 6281 (ICC 1989), reprinted in 15 Y.B. COM. ARB. 96 (1990); Final Award No. 6527 (ICC 1991), reprinted in 18 Y.B. COM. ARB. 44, 45-47 (1993)).

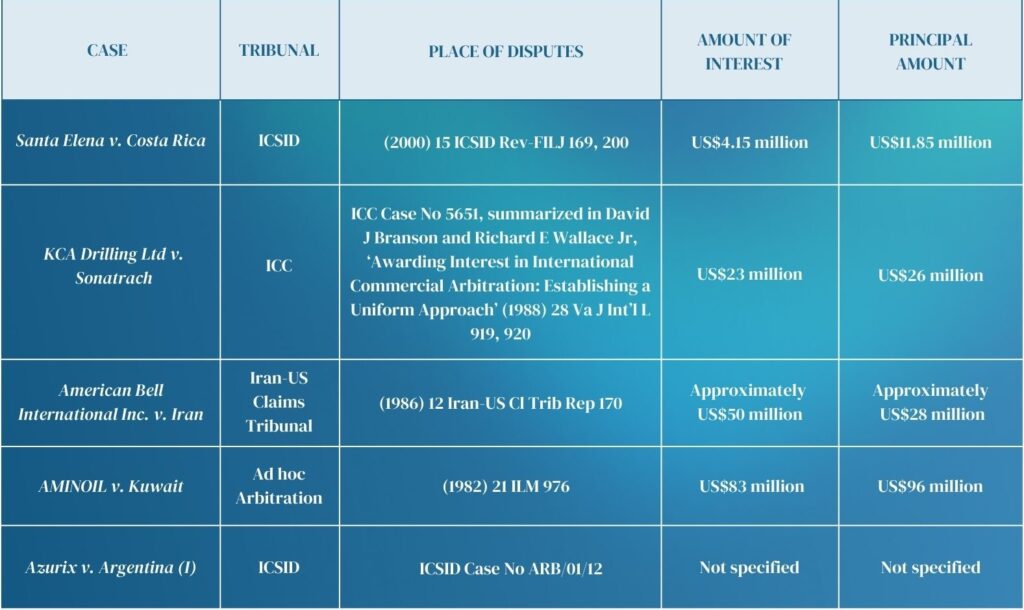

The opacity surrounding the interest rate can present significant challenges, particularly in cases involving substantial sums and prolonged delays (American Bell Int’l Inc. v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 12 Iran-U.S. Cl. Trib. Rep. 170, 229-31 (1986) (awarding approximately $28 million in interest on damages of approximately $50 million); AMINOIL v. Kuwait, Final Award, 24 March 1982 (awarding $96 million in interest on $83 million in damages).

Notable areas of uncertainty include:

- The uncertainty surrounding the permissibility of awarding compound interest instead of simple interest;

- The appropriateness of applying a fixed commercial rate versus a floating commercial rate; and

- The determination of the optimal date from which interest should be calculated.

The financial implications of awarding interest can be as substantial as the principal claim itself, especially when extensive delays and large amounts are involved (J. Gillis Wetter, Interest as an Element of Damages in the Arbitral Process, INT’L FIN. L. REV., Dec. 1986, at 22; Richard B. Lillich, Interest in the Law of International Claims, in essay in Honor of Voitto Saario and Toivo Sainio 52 (1983)). For instance, in Tenaris v. Venezuela, Award, 29 January 2016 the tribunal awarded $87.3 million in principal damages, while the interest accrued during the arbitration amounted to $85.5 million, reflecting an eight-year arbitration process.

The table below illustrates how the awarded interest can, in certain circumstances, rival or even surpass the principal amount in dispute. This phenomenon occurs particularly in cases where there are substantial delays in rendering the final award or where compounded interest is applied over an extended period.

The Methodology Behind Interest Rate Calculation

Generally, the calculation of interest in arbitration is determined by three factors:

- The principal amount awarded,

- The period during which the payment is due, and

- The applicable interest rate.

While the principal depends on the claim and the tribunal’s award, the time factor is crucial, often leading to substantial interest amounts (Supra J. Gillis Wetter). However, shorter arbitration durations, though potentially reducing interest, could limit the arbitrators’ ability to thoroughly analyze the case, thus risking the quality of the decision. Despite the availability of expedited procedures, their use remains rare (Interest in International Arbitration (2021), Ch.1, paras 1.01–1.03).

In this context, three primary challenges related to interest rates that are worth exploring include establishing the start date for interest accrual, choosing an appropriate calculation method, and determining the most effective rate to apply.

The Application of Choice of Law Analysis in Interest Rate

When arbitrators address the rate of interest, they usually look to the parties’ agreement for any provisions explicitly addressing these issues (Bechtel, Inc. v. Iran, Award No. 294-181-1, 4 March 1987 and ICC Case No. 6230, Final Award, 1990). However, if the agreement is silent or ambiguous regarding interest, the arbitrator usually performs a choice-of-law analysis to select the law of a particular country and apply it to resolve the interest claim (ICC Case No. 6281, Final Award, 1989 and ICC Case No. 6527, Final Award, 1991). Conflict of law analysis allows tribunals to balance local statutory rates with broader commercial considerations.

In both American Bell Int’l Inc. v. Iran and Aminoil v. Kuwait, tribunals employed conflict of law analysis to determine appropriate interest rates by assessing relevant domestic laws, international principles, and commercial practices. This approach helps tribunals navigate conflicting legal frameworks to ensure the interest awarded aligns with economic realities. In American Bell, the tribunal awarded $28 million in interest on $50 million in damages, while in AMINOIL, $96 million in interest was awarded on $83 million in damages.

The exercise of choice-of-law analysis carries its challenges, particularly with the lack of clarity on key issues, including whether compound interest can be awarded over simple interest and whether a fixed or floating commercial rate is more appropriate, especially in cases involving large sums and extended delays. In Santa Elena v. Costa Rica, the tribunal used conflict of law analysis to navigate between Costa Rican national laws and international legal principles governing expropriation and compensation. The tribunal ultimately dismissed the relevance of national law and relied on international law, emphasizing the need for “full reparation” as required by the Factory at Chorzów (PCIJ Series A. No 17), Judgment, 13 September 1928 and customary international law. This led to the decision to award compound interest, which was deemed more appropriate for ensuring ‘full compensation’ for the expropriated property, reflecting a shift from the traditionally applied simple interest in such disputes.

The Utility of CISG in Determination of Interest Rate

When determining interest rates, tribunals typically follow a structured approach. They first examine the relevant local law to identify any statutory provisions or contractual agreements between the parties. If local law is unclear or insufficient, tribunals then turn to international conventions (such as the United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) (1980)) and customary international law to fill gaps.

The following are the key considerations concerning the aptitude of CISG in tackling the complexities of interest rate:

- CISG aims to harmonize trade and investment regulations (Peter Schlechtriem, ‘Introduction’ in Peter Schlechtriem and Ingeborg Schwenzer (eds), Commentary on the UN Convention on the International Sale of Goods (CISG)), however, the provisions concerning damages and interest rates are quite vague.

- Article 74 of the CISG stipulates that the damages should equal the “loss suffered,” embodying the principle of full compensation. Article 78 entitles parties to interest on unpaid sums but lacks a method for calculating interest.

- The lack of clarity leads to inconsistent application across jurisdictions, applying domestic law while others apply general legal principles (Harry Flechtner and Joseph Lookofsky, ‘Viva Zapata! American Procedure and CISG Substance in a U.S. Circuit Court of Appeal’ (2003) 7 Vindobona Journal of International Commercial Law and Arbitration 93). The lack of clarity over the general guidelines for interest rate is significantly pronounced in two critical issues: the proof required to recover damages and how interest is calculated.

- Article 7(2) of the CISG guides tribunals to use the Convention’s general principles to fill gaps, maintaining consistency in international sales law.

Burden of Proof in Interest Rate Review

The Convention does not explicitly specify the level of proof required to recover damages under Article 74. The court in Delchi Carrier SpA v. Rotorex Corp., 71 F.3d 1024 (2d Cir. 1995), have treated it as a procedural matter and applied local law, requiring that damages be proven with reasonable certainty. A key caveat of applying national laws to determine the level of proof under Article 74 is that it leads to inconsistent treatment of similar cases, as different jurisdictions have varying standards of proof and distinctions between procedural and substantive law.

- In common law countries, claimants must prove certainty of damages with reasonable certainty, such as under Indian law where a reasonable estimate of loss suffices (ICC Final Award in Case No. 78445, reprinted in 26 Y.B. COM. ARB. 167, 175 (2001) (citing State of Kerala v. K. Bhaskaran, AIR (1985) Kerala 55)).

- In civil law countries like Switzerland, claimants must prove damages, with a high standard of proof for lost profits (Code des obligations [Co] [Code of Obligations] art. 42 (Switz.) (applying to determine damages for breach of contract pursuant to article 99 of Code of Obligation)).

- Whether the level of proof is substantive, or procedural varies by jurisdiction, such as in Italy’s Civil Code versus Switzerland and Germany, where it’s procedural (Sun Oil Co. v. Wortman, 486 U.S. 717, 726 (1998) “Except at the extremes, the terms ‘substance’ and ‘procedure’ precisely describe very little except dichotomy, and what they mean in a particular context is largely determined by the purposes for which the dichotomy is drawn.”).

- Requiring damages to be proven with reasonable certainty aligns with UNIDROIT Principles. Article 7.4.3 requires compensation for harm, including future harm, to be established with reasonable certainty (UNIDROIT (International Institute for the Unification of Private Law) Principles of International Commercial Contracts (2016), art. 7.4.3.).

This section has established that public international law and the CISG lack coherent guidelines for the quantification of interest rates and the challenges associated with them. Building on this foundation, the second part will provide clear insights into the shortcomings of conflict of law analysis in addressing critical dichotomies. These include the divide between commercial and fixed rates, the application of compound interest, and the inconsistencies between domestic legal frameworks and the public international law regime

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Naimeh Masumy is a PhD Candidate at Maastricht University and a Research Fellow at Deakin University. In her professional capacity, she advises on international trade, regulatory compliance, and arbitration under ICC and UNCITRAL rules. Naimeh serves on the International Transnational Arbitration Advisory Board and the editorial board of ITA in Review. She holds an LLM in international banking and finance law from University College London and a degree in international legal studies from the University of Pennsylvania.

*The views and opinions expressed by authors are theirs and do not necessarily reflect those of their organizations, employers, or Daily Jus, Jus Mundi, or Jus Connect.